All the sanitation improvement projects and investments over the years beg the question of whether we have seen a significant increase in school enrollment and gender parity in education or not. While most empirical studies on sanitation focus on the relationship between sanitation and health, recent studies have now looked into the downstream impacts of sanitation on other development indicators, such as those related with education and gender.

In much of the developing world, sanitation remains a serious issue. Households and schools that lack working toilet facilities may affect girls’ and boys’ schooling unfavorably. In India, for instance, where 23% of the world’s out-of-school children (aged 6–17 years) reside (UNESCO Institute for Statistics 2016), thousands of schools still do not have gender-specific or even unisex toilets. In places where latrines are available, cleaning and maintaining facilities pose further challenges. Adukia (2017), using a difference-in-difference approach, notes that the construction of toilets across schools in India in 2003 led to a significant rise in student enrollment, with girls exhibiting a higher increase in enrollment than boys at both the primary and upper-primary levels. Interestingly, compared with unisex latrines, the provision of gender-specific latrines yields a higher positive impact on girls’ enrollment. This is especially true in upper-primary schools, indicating that girls tend to value safety and privacy more as they grow older.

Further, Garn et al. (2013) employ a randomized control trial to explore the impact of water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH) projects across schools in Nyanza, Kenya. They report a significant increase in school participation, especially among girls. In terms of cognitive skills, Orgill-Meyer and Pattanayak (2020) mention that an increase in the number of latrines in rural Odisha, India, improved children’s test scores a decade later. The effect on academic scores is again substantially higher among girls than boys.

Hence, the bulk of the recent empirical evidence on the linkages among sanitation, education, and gender convey a similar message—girls benefit more from improved sanitation access than boys.

There are many pathways through which proper sanitation services affect girls’ schooling. First, they ensure girls’ safety and privacy, allowing them to avoid going to dark and silent corners when they need to relieve themselves. Likewise, if latrines are available at a close distance, girls become less exposed to dangerous situations that may put them at risk of physical harm, bullying, or sexual assault. Second, sanitation initiatives support menstrual hygiene management, which means that girls do not have to skip school (by at least 5 days in a month) since toilet and washing facilities are readily available. Third, female teachers also benefit from accessible sanitation services in the same way that younger girls do. This means that they can always be present and focused at work. Since female students see female teachers as role models and, in many cases, feel more comfortable around them, female students are motivated to go to school.

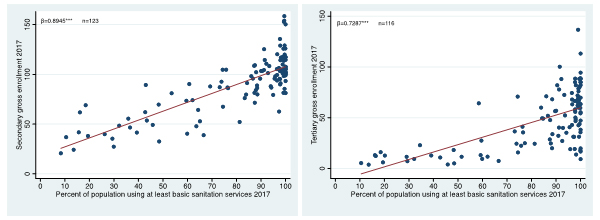

Using country-level data, simple regression analyses reveal a significant correlation between access to basic sanitation and the enrollment of girls and boys, both at the secondary and tertiary levels in 2017 (Figure 1). Consistent with the findings mentioned above, this positive association suggests that sanitation facilities allow children to better focus on their schooling since they worry less about their basic needs and start to gain better health outcomes.

Figure 1: Basic Sanitation and Enrollment in Secondary and Tertiary Education, 2017

Note: “At least basic sanitation services” refers to improved sanitation facilities, including flush/pour flush to piped sewer systems, septic tanks or pit latrines, ventilated improved pit latrines, composting toilets, or pit latrines with slabs. *** indicates significance at the 1% level.

Source: Authors’ calculations. Data gathered from the World Health Organization/UNICEF Joint Monitoring Programme for Water Supply, Sanitation and Hygiene and UNESCO Institute for Statistics.

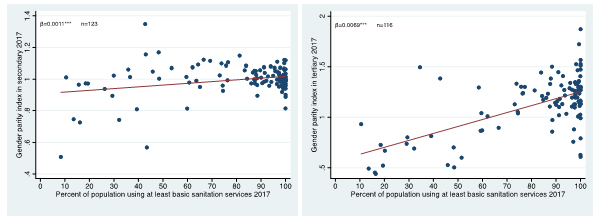

Notably, the significant and positive relationship between sanitation access and the gender parity index (GPI) in secondary and tertiary schooling (Figure 2) may indicate how girls are able to catch up with boys in school participation as sanitation services improve. Girls are especially reliant on gender-specific and hygienic sanitation facilities as they enter puberty, when they also start to experience regular monthly periods. In developing countries, a lack of separate toilets can cause adolescent girls to skip school.

Figure 2: Basic Sanitation and Gender Parity Index in Secondary and Tertiary Enrollment, 2017

Note: The gender parity index in secondary or tertiary gross enrollment is the ratio of girls to boys enrolled at the secondary or tertiary levels in public and private schools. *** indicates significance at the 1% level.

Source: Authors’ calculations. Data gathered from the World Health Organization/UNICEF Joint Monitoring Programme for Water Supply, Sanitation and Hygiene and UNESCO Institute for Statistics.

From a development perspective, more evidence-based research on sanitation that uses gender-disaggregated data could be useful for practitioners and policy makers in (i) selecting areas or locations that must be prioritized, (ii) determining the most disadvantaged groups that need immediate assistance, and (iii) pointing out where investments and efforts are lacking. Gender-based action plans are critical in envisioning an inclusive future for sanitation.

Conclusively, the linkages among sanitation, education, and gender require further scrutiny. As more data from the field become available, more opportunities for micro-level evaluation arise. So far, a clear pattern is evident—when children’s sanitation needs are met, the benefits to human capital encompass not only better health and nutrition but also higher enrollment and lower gender gaps in school participation.

_____

References:

Adukia, A. 2017. Sanitation and Education. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 9(2): 23–59.

Garn, J. V., L. E. Greene, R. Dreibelbis, S. Saboori, R. D. Rheingans, and M. C. Freeman. 2013 A Cluster-Randomized Trial Assessing the Impact of School Water, Sanitation and Hygiene Improvements on Pupil Enrolment and Gender Parity in Enrolment.Journal of Water, Sanitation and Hygiene for Development,3(4): 592–601.

Orgill-Meyer, J., and S. K. Pattanayak. 2020. Improved Sanitation Increases Long-Term Cognitive Test Scores. World Development, 132: 104975.

UNESCO Institute for Statistics. 2016. Leaving No One Behind: How Far on the Way to Universal Primary and Secondary Education? Policy Paper 27 / Fact Sheet 37, July, 2016.

Photo source: By Asian Development Bank.

Comments are closed.