The disappointing scale-back of California’s showcase high-speed rail system between San Francisco and Anaheim has many experts asking what lessons can be learned. Similar pushbacks have occurred on other continents: witness the popular resistance to construction of a new superstation as part of Stuttgart’s urban renewal, which escalated into violent demonstrations, delays, and stalemates. Megaprojects worldwide encounter opposition from the very people they aim to serve.

Developing countries without the open expanses of, e.g., Central Asia or parts of the People’s Republic of China, often point to their difficulties in buying a right-of-way corridor through crowded cities or confusing, multiple smallholder farm plots along which a highway or rail project is planned. (Usually rail rights-of-way run along ground-level, i.e. at-grade, which for our purposes includes embankments and cuttings that permanently change the topography).

There are many reasons for these difficulties, just as each country’s socio-political and land use history is diverse and defies easy stylization (Table 1).

Table 1: Difficulties in Securing Rights-of-Way for Public Transport

| Main problem | Reasons | Ease of Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Poor or no land titling; unclear, contesting owners | History; land reform; society dispossessed or war-torn | Long term; nation- or state-wide reforms are best |

| Indigenous/squatters; stewardship of nature | Conflict in land use views; respect and reparations | Often intractable; politically unpalatable; losers resent |

| No or slow eminent domain/forced sales | Different legal tradition; weak courts; lack of trust | Usually long term; multi-generational wait |

| Unpredictable zoning; unfair to first movers/first peoples | Religious or cultural uses; original use vs. new plans | Medium term; improve consultation/voice stages |

| Uncertain if land gets used for planned public purpose | Many risks of projects stalling, greater in DMCs | At preplan and build stages;believable guarantor helps |

| Suspicion of governance and process transparency; insensitive involuntary resettlement | History; stage of rule of law; distrust of elites; lack of capacity or respect for safeguards | Usually long term; nation- or state-wide level reform best; immediate role for IFIs to improve capacities |

DMCs = developing member countries; IFIs = international finance institutions.

Source: Authors; Fukuyama and Yoshino (2019).

Next comes the obvious but little remarked innate endowment of basic geography. Projects in big countries like Spain, Canada, and Australia often benefit from large landowners (Table 2), who are easily able to cede a small portion of their vast holdings for a public transport purpose and keep and enjoy the remainder of their property relatively undisturbed. Understandably, if you are asking a poorer smallholder who only has that modest plot to live on and cultivate for themselves and their families, the chance of non-acceptance will always be greater. Add to that, if the smallholder is a long-time member of a nurturing village or thriving ethnic community, they are also going to be more cautious about taking the chance of being split up or relocated from their friends and neighbors.

Table 2: Comparison of Rail Tracks Laid in Select Countries by Farm Size and Population Density

| Country | Average Farm Size (from largest to smallest; hectares) | Population Density (per square kilometer) | Track Length (kilometers) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Australia | 4,331 (2016) | 3.1 (2016) | 33,343 (2015) |

| Canada | 314.84 (2011) | 4 (2018) | 77,932 (2014) |

| Spain | 25.4 (2010) | 94 (2018) | 15,302 (2017) |

| Thailand | 3.15 (2013) | 135.8 (2018) | 4,127 (2017) |

| Pakistan | 2.58 (2010) | 275 (2018) | 11,881 (2019) |

| Georgia | 1.4 (2014) | 65.2 (2018) | 1,363 (2014) |

| Philippines | 1.29 (2012) | 337 (2015) | 77 (2017) |

| India | 1.08 (2016) | 454.9 (2018) | 68,525 (2014) |

| Viet Nam | 0.188 (2014) | 308.1 (2018) | 2,600 (2014) |

Sources: As cited under each hyperlink. Years for latest data in parentheses.

In addition, the length of time during which the transportation technology has been in use will be another determinant. If a country has a long history of railroads,1 chances are it will have been able to lay enough legacy tracks and obtain sufficient rights-of-way when the areas were not so built-up, or following regrettable windows of opportunity caused by natural or man-made disasters which allow a second chance for more organized easements.

If promoters can plan out their high-speed routes to take advantage of existing freight lines or underused or abandoned tracks, then securing the guideway becomes much faster and less complicated. Other factors favoring success include linking naturally complementary cities not too far apart or separated by challenging terrain, such as Tokyo with (Shin-)Osaka, New York to Washington, DC, or Mumbai to Ahmedabad (though India’s impressive legacy rail network is a rarity in developing countries).

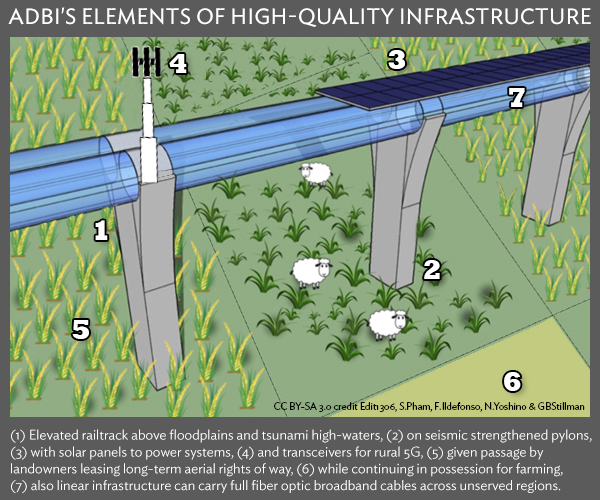

Finally, cutting-edge technology is coming to the aid of getting around rights-of-way bottlenecks. Today’s maglev and high-speed trains traverse elevated tracks on spanning viaducts supported by pylons with much smaller footprints on the rural landscape. Just as high-voltage transmission towers can allow planting of crops and animals to graze around their base, modern railway support columns are engineered to require smaller foundational areas, preserving the claims of farmland of smallholders underneath (diagram).

Elements of high-quality infrastructure that accommodates social and environmental concerns while minimizing disruptions and resettlement: Seismic-strengthened pylons minimize the ecological footprint of elevated (above floodplain) railway over conserved farmlands, allowing for reduced crop cultivation and the grazing of herds by smallholders continuing in possession while leasing aerial rights-of-way. Note also solar panel placement to power systems and contribute excess electricity to nearby farms and off-grid communities. Pylons can even perform a double duty by supporting 5G transceivers and carrying full fiber optic broadband cables across unserved areas, opening another revenue stream. Diagram by Edit1306 after SpaceX, available Wikimedia Commons; 5G and ground elements remixed by Sarah Pham. CC BY-SA 3.0.

Sources: Yoshino et al. 2019; T20 Summit Communique 2019, Task Force 4; Susantono 2019; authors.

At the other extreme, engineers in Europe, the Americas, and Asia are recognized for their experience with railway and highway tunneling. Moreover, the costs and time of tunnel boring will continue to be reduced by advancing carbon-lite technologies. Yet even underground routes have the potential to cause nuisance (particularly during construction), are not free from technical barriers, and can therefore encounter objections by ground-dwellers or owners of property above.2

Precursor of the hyperloop principle? A full-scale pneumatic tube transit demonstration of atmospheric propulsion under the streets of New York circa 1873. (“The only new thing in the world is the history you don’t know.”) Credit: Wikimedia Commons.

A mixture of elevated and underground sections will also be better for climate and disaster resilience, land and water conservation, reduction of deforestation and air, noise and visual pollution, less disruptive of animals’ grazing paths and access to habitat, as well as safer and more efficient for the separation of pedestrians and car traffic from busy at-grade crossings. These criteria will be used to evaluate the lifecycle efficiency of future rail systems, such as the ADB-JICA-supported Malolos-Clark Railway Project.

Instead of resorting to traditional confrontational compulsory acquisitions with the distress caused by relocations, new ways to package and pool smallholder lots and easements through equitable readjustments, reallocations, exchanges, or reversionary rehabilitation schemes are being tried by communities with the support of land trusts, banks, and sympathetic renewal authorities (Yoshino et al. 2019).

In megacities like Tokyo, individuals who occupy small houses often increase the utility of their land by consolidating their property with neighbors and erecting apartments or office buildings on it. Usually, the landowners entrust their land to the trust bank, which develops the consolidated properties to use them more effectively. Sometimes the participating landowners can live in apartments within the building and receive part of the profits as dividends from the trust bank. Assuming breakeven occupation and sufficient rental revenues, individual landowners can generate greater profit by this collective method. Similarly, an agricultural trust bank can manage the rural landowners’ collective properties. Another option might be a registered transfer of only certain usage rights over the land to the trust bank. This way, landowners can maintain ownership of the land yet increase their profit by lending the land to other users, including railways, through trust banks (Yoshino and Paul 2019).

More needs to be done to implement ADBI Dean Naoyuki Yoshino’s proposal for using long-term leases to secure sections of guideways with options to buy at the end of 40 or 99 years. This approach could allow landowners, first peoples, or informal settlers in the way of a development to retain their (and their heirs’) legal interest in or connection to the land, without vetoing the optimal path or placing a rent-seeking stranglehold over future operations when the lease comes up for renewal.

The solution for quickly lining up rights-of-way in crowded places is not always at-grade, pushing aside everything in its path; nor necessarily elevated tracks on spanning viaducts or burrowing endless underground tubes. Rather, an imaginative, respectful and utilitarian amalgam of all three dimensions building on existing, repurposed track paths is preferable. That is, until we can find a way to move people through four-dimensional space. Any ideas, Mr. Musk?

_____

1 For instance, Canada, Spain, Australia and India were all early adopters of rail, dating back between 165 to 180 years ago.

2 Very deep tunnels passing well beneath a building’s foundations or useable subterranean levels might not even need to purchase underground rights or permissions from the surface landowner depending on limitation regimes established by local law. See further discussion on superficies in Principles of Infrastructure: Case Studies and Best Practices (Nakamura et al. 2019: 257).

References:

ADB News. 2019. Malolos-Clark Railway Project: North-South Commuter Railway, PNR Clark – Phase 2. July Infographic. Asian Development Bank.

Asian Institute of Transport Development and ADBI. 2019. High Speed Rail Services in Asia (A Joint Publication of ADBI and AITD). Special January Issue. The Asian Journal of Transport and Infrastructure 1. New Delhi.

Burrows, D. 2019. Northern California Preferred HS Route Options Revealed. July, International Railway Journal.

Fukuyama, F., and N. Yoshino. 2019. How to Thread the Economic and Political Needle on Asian Infrastructure Growth. Podcast. Asian Development Bank Institute.

Hickman, M. 2017. First Fully Solar-Powered Train Hits the Track—Restored Rail Line Meets Clean Technology in Australia’s Byron Bay. December. MNN.com Tech channel.

Hossain, M. and N. Yoshino, Implementing Land Trust in Bangladesh: A Strategy for Financing Infrastructures and Sustainable Management. (forthcoming). Tokyo: Asian Development Bank Institute.

Nakamura, H., K. Nagasawa, K. Hiraishi, A. Hasegawa, KE Seetha Ram, C.J. Kim, and K. Xu. 2019. Principles of Infrastructure: Case Studies and Best Practices. Tokyo: Asian Development Bank Institute.

Rothengatter, W. 2019. Approaches to Measure the Wider Economic Impacts of High-Speed Rail and Experiences from Europe. ADBI Working Paper 946. Tokyo: Asian Development Bank Institute.

Slowey, K. 2019. What Future High-Speed Rail Developers Can Learn from the California Bullet Train. Construction Dive. May Newsletter.

Susantono, B. 2019. Metros Push Up Land Values—So Why Not Create A Triple Win? May. Manila: Asian Development Bank.

T20 Summit. 2019. Communique, 10 June. Tokyo. Recommendations of Task Force 4 on Economic Effects of Infrastructure Investment and its Financing, p.8.

Yoshino, N., S. Paul, V. Sarma, and S. Lakhia. 2019. Land Trust to Facilitate Development Through Land Transfer. In Land Acquisition in Asia: Towards a Sustainable Policy Framework, edited by N. Yoshino, and S. Paul. Singapore: Palgrave Macmillan.

Yoshino, N., N. Hendriyetty, and S. Lakhia. 2019. Quality Infrastructure Investment: Ways to Increase the Rate of Return for Infrastructure Investments. ADBI Working Paper 932. Tokyo: Asian Development Bank Institute.

Comments are closed.