Increasing reliance on international trade as an economic driver has spurred the emergence of e-commerce through rapid digital technology innovation. Cross-border e-commerce (CBEC) conducted via the Internet can enhance trade efficiency, reshape global value chains, and expand market access for producers (Wang 2014), lowering trade barriers and stimulating trade growth (Terzi 2011). The global CBEC sector has exhibited significant growth, and a 37.6% increase is projected over the next 5 years, driven by digital technology innovation addressing traditional trade challenges.

Growth in CBEC can stimulate competition and the adoption of state-of-the-art technologies, increasing competitive advantage. Albeit at an early stage, the increasing adoption of artificial intelligence (AI) in e-commerce businesses aims to provide a personalized shopping experience, optimize inventory management and logistics, detect and prevent fraudulent activity, and drive growth. AI algorithms increase the likelihood of customer conversion by analyzing big data on purchase history, browsing behavior, and search queries to recommend products tailored to individual customer preferences through enhanced customer engagement (Lari, Vaishnava, and Manu 2022). AI algorithms based on consumer behavior patterns create effective recommendation systems, while AI chatbots free up human customer service representatives to handle more complex inquiries, improving efficiency and cost savings services 24-7. Moreover, AI-enabled cloud services are being used to detect conversion fraud, ensure transparency, safeguard transactions, and win customer trust. These advancements in AI technology have significantly impacted the efficiency and growth of the e-commerce industry.

Despite the numerous advantages of AI technology in e-commerce, skepticism has arisen from media reports highlighting AI’s failures. Uncertainty associated with the development and deployment of AI in e-commerce can also cause distrust. Trust plays a pivotal role in adopting and using AI in e-commerce, and research has consistently highlighted the mediating role of trust in the interaction between humans and technology (Ba and Pavlou 2002; Cabrera-Sánchez et al. 2020). Trust is a critical precursor to risk-taking behavior and can mitigate perceived uncertainty and influence customers to select products or services these technologies provide, fostering long-term relationships with businesses that employ AI.

Although the evolution of CBEC can help to meet increasing demand, consumer perception and perceived trust remain critical for stakeholders to stimulate growth (Pavlou 2006). Customer trust is conditional on product quality, availability, price, shipping, and payment options. This trust is built through personal experience and recommendations, and a transaction can only be completed once it reaches a critical level (Kundu and Datta 2015).

Trust in CBEC encompasses trust in products and services and the transaction mechanism. Consumers derive trust from customer feedback and brands, whereas perceived trust in the transaction mechanism is conditional on various other factors, including technological, cultural, legal, and ideological disparities across countries. Since CBEC involves multiple stakeholders, understanding its generic structure is essential for addressing trust challenges and ensuring its success.

After receiving an order through an e-commerce platform, a seller processes the payment, completes packaging, and ships it through their own or third-party logistics (3PL) provider. After customs clearance, the order is delivered through the local logistics provider. Therefore, a successful delivery is conditional on trust at each transaction level.

Navigating trust hurdles

Quality of products and services. A lack of product transparency and seller reputation awareness breeds suspicion regarding quality, and this can be compounded by market complexity. Uncertainty extends to service transactions, amplified by trust concerns in transaction mechanisms and regulations. Stakeholder consensus on AI adoption and communication is, thus, pivotal for transaction efficacy.

- Hostility in cyberspace. Cyber threats like DDoS and phishing can impede CBEC expansion (Mishra 2022), prompting e-commerce firms to fortify cybersecurity (Vinoth et al. 2022). Government policies augment operational costs (Luo and Choi 2022) and reduce CBEC effectiveness.

- Opaque cross-border logistics. Cross-border logistics is opaque due to the absence of a tracking system, language barriers, and regulatory complexities, and it hinders CBEC logistics, especially in unfamiliar international settings without global standards.

- Heterogeneous regulatory issues. Divergent standards and regulations across countries delay CBEC transactions, exacerbating uncertainties and costs. Inadequate consumer protection and dispute resolution mechanisms heighten fraud risks. Technological solutions can mitigate these challenges, fostering CBEC trust and growth.

Anthropomorphism of AI in safeguarding trust in CBEC

Researchers argue that AI can significantly build trust in CBEC by detecting fraudulent activities, maintaining users’ privacy, and ensuring compliance with regulations. However, the challenges are multifaceted and can include the concept of anthropomorphism.

Anthropomorphism is the process of incorporating human-like qualities into AI systems, and research suggests that individuals are more likely to trust and accept AI that exhibits human-like characteristics (Waytz, Heafner, and Epley 2014). However, over-anthropomorphization can lead to an exaggerated perception of an AI’s competencies, which may pose risks to stakeholders (Culley and Madhavan 2013). This can damage trust and result in various ethical and psychological concerns, including manipulation (Sallesa, Eversa, and Farisco 2020). Therefore, the use of AI is not simple and requires developing trust among stakeholders and users.

Strategic use of digital technology in enhancing trust in CBEC

- Identity and information asymmetry. Blockchain technology can reduce information asymmetry through enhanced transparency and accountability by creating and verifying the digital identity of CBEC participants, which is the root cause of fraud and identity theft. Moreover, implementing and integrating multi-layered identity verification and authentication for stakeholders’ citizen IDs, digital financial IDs (for verifying bank account information) and fiscal IDs (for tax return of information) can enhance the possibilities of cross-border transactions without altering the respective governments’ regulations.

- Buyers’ feedback. Customers seek to establish trust regarding a product or brand from through feedback (Li et al. 2019). With various Web 2.0 applications, AI, and big data, stakeholders can collect, monitor, and analyze product information and feedback, providing quality assurance and certification (Yin and Choi 2021) by capturing the real opinions and evolutions of products and services. Moreover, countries with CBEC may adopt cookie consent from users or visitors to protect privacy, as mentioned in the European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR).

- Value chain and logistics. CBEC logistics operates under heterogeneous social, economic, and structural conditions, resulting in low efficiency and high costs. With a new decentralized structure for common data maintenance, distributed storage, and cryptography, AI can resolve this issue by ensuring the safety of data transmission and irreversibility. Furthermore, the Internet of Things can automate and track the shipment and delivery of CBEC goods and provide real-time updates to reduce the delivery system’s risk and enhance the stakeholders’ trust.

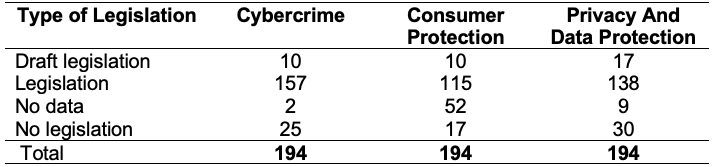

Regulatory challenges. Establishing robust regulatory frameworks and adhering to international standards are essential for building CBEC trust. Clear, consistent, and enforceable policies contribute to sustainable CBEC and stress the need for regulatory frameworks (UNCTAD 2020; European Commission 2017). Table 1 shows the current status of regulatory frameworks across countries. However, the nature of these data privacy laws can vary depending on the prevailing status of the digitalization of the respective countries. Therefore, there is a need for cooperation and the formulation of a universal law.

Table 1: Number of Countries with Data Privacy Laws, 2023

Source: UNCTAD.

Universal data regulation on data privacy requires data harmonization to unify disparate data fields, formats, dimensions, and columns into a composite dataset. Data harmonization ensures that data is consistent, accurate, and compliant with different jurisdictions’ relevant laws and regulations while facilitating sharing and allowing interoperability across entities and systems.

The way forward

The continuous growth of CBEC, driven by consumer demand, international trade, and favorable policies, has made it a dynamic force in Asia. It presents immense opportunities for businesses and economies across the region. The multi-layered and multi-functional composition and multiple stakeholders with heterogeneous objectives and backgrounds make the structure of CBEC complex, and trust is a critical driving factor. The advancement of digital technologies can reduce risks, enhance trust, and foster CBEC growth. However, implementing these technologies requires countries to cooperate in formulating international data privacy standards. Regulation on the use of digital technologies, especially AI, and collaborative efforts among all stakeholders can cultivate a secure and trustworthy environment, unlocking the full potential of CBEC.

References

Ba, S., and P. A. Pavlou. 2002. Evidence of Trust Building Technology in Electronic Markets: Price Premiums and Buyer Behavior. MIS Quarterly 26(3): 243–268.

Cabrera-Sánchez, J.-P., I. Ramos-de-Luna, E. Carvajal-Trujillo, and A. Villarejo-Ramos. 2020. Online Recommendation Systems: Factors Influencing Use in E-Commerce. Sustainability 12, 8888.

Culley, K. E., and P. Madhavan. 2013. A Note of Caution Regarding Anthropomorphism in HCI Agents. Computers in Human Behavior 29(3), 577–579.

Kundu, S., and S. Datta. 2015. Impact of Trust on the Relationship of E-Service Quality and Customer Satisfaction. EuroMed Journal of Business 10(1): 21–46.

Lari, H. A., K. Vaishnava, and K. S. Manu. 2022. Artifical Intelligence in E-commerce: Applications, Implications and Challenges. Asian Journal of Management 13(3). https://doi.org/10.52711/2321-5763.2022.00041

Luo, S., and T. Choi. 2022. E-Commerce Supply Chains with Considerations of Cyber-Security: Should Governments Play a Role? Production and Operation Management 31: 2107–2126. https://doi.org/10.1111/poms.13666

Mishra, A. A. 2022. Cybersecurity Enterprises Policies: A Comparative Study. Sensors 22: 538. https://doi.org/10.3390/s22020538.

Pavlou, P. A. 2006. The Nature and Role of Feedback Text Comments in Online Marketplaces: Implications for Trust Building, Price Premiums, and Seller Differentiation. Information Systems Research: 392–414.

Sallesa, A., K. Eversa, and M. Farisco. 2020. Anthropomorphism in AI. AJOB Neuroscience 11(2): 88–95. https://doi.org/10.1080/21507740.2020.1740350

Terzi, N. 2011. The Impact of E-Commerce on International Trade and Employment. Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences 24: 745–753.

Vinoth, S., H. Vemula, B. Haralayya, P. Mamgain, M. Hasan, and M. Naved. 2022. Application of Cloud Computing in Banking and E-Commerce and Related Security Threats. Mater. Today Proc.: 2172–2175.

Wang, J. 2014. Opportunities and Challenges of International e-Commerce in the Pilot areas of China. International Journal of Marketing Studies 12(2): 141–149.

Waytz, A., J. Heafner, and N. Epley. 2014. The Mind in the Machine: Anthropomorphism Increases Trust in an Autonomous Vehicle. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 52: 113–117. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2014.01.005

Yin, Z. H., and C. H. Choi. 2021. The Effects of China’s Cross-Border E-Commerce on Its Exports: A Comparative Analysis of Goods and Services Trade. Electronic Commerce Research: 443–474.