As we now increasingly rely on technical innovations to solve some of society’s most complex problems, technological advancements such as artificial intelligence are contributing to new, modern modes of transportation, especially to enhancing safety. However, technology is only one of many critical factors for safety, and there is a need to understand the other factors.

The Mumbai–Ahmedabad High-Speed Railway (HSR) is adopting Japanese railway technology, which is renowned for its remarkable performance and record of zero fatal accidents in more than 50 years of operation. HSR is also a complex socio-technical system in which humans and technology work seamlessly to assure impeccable safety performance. This coordination between humans and technology is fragile, however. Thus, prior to implementation in India, the technology must be carefully investigated given that the national railway system was involved in more than 29,000 incidents in 2015.

At the 15th World Conference on Transport Research in Mumbai in May 2019, the special session organized by the Asian Development Bank Institute entitled “Need for HSR and Importance of Dedicated Track towards Safe, Available and Reliable Operations” brought together practitioners, academics, and policy makers to discuss how the safety and reliability of HSR operations could be achieved. Mr. Yoshihiro Kumamoto from East Japan Railway Company and Mr. Byung-il Oh from the Korea Railroad Corporation shared their experiences from their countries. Mr. Venkitachalam, a safety professional at the Indian Institute of Technology Gandhinagar, provided an overview of the current status of the railway safety in India. Their presentations captured the essentials of the safety management principles from the HSR systems in Japan and the Republic of Korea and identified the scope of improvements for countries newly adopting HSR, such as India.

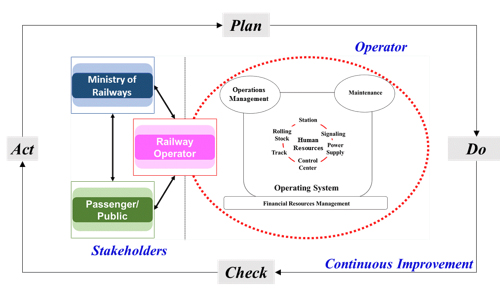

Figure 1 summarizes the basic principles of HSR safety management in Japan and the Republic of Korea using the principles of systems thinking, where safety is achieved through dynamic interactions between various parts and components of HSR. We can extract three key messages.

Figure 1: Systems Thinking Framework for High-Speed Rail Safety

Source: Author.

The first message relates to the stakeholders in safety management for HSR. Although the HSR operator plays a critical role in safety, just as crucial are the functions of the top regulator (e.g., the Ministry of Railways) and the passengers or public. The regulator sets the appropriate safety standards and ensures that these are complied with during the various stages of the HSR development and operations. That is, the regulator approves the different safety management plans prepared by the HSR operator. Inefficiency in the effective management of these standards can inevitably lead to a fatal accident. Additionally, the behavior of passengers and the public can affect HSR safety. In Japan, for example, passengers boarding a train always wait in an orderly line, which minimizes the disturbance to alighting passengers, thus creating a smooth passenger flow and reducing the risk of incidents on the platforms, such as passengers falling.

The second message relates to the responsibilities of the HSR operator. Having reliable, state-of-the-art technology is certainly important for achieving safety. For example, both in the Japanese and Korean HSR systems, operators have installed numerous sensors to closely monitor weather conditions and seismographs to detect earthquakes that are designed stop train operations at the earliest detection of warning signs. However, installing state-of-the-art technology alone is not enough—operators must work to continually maintain their assets (bridges, tracks, rolling stock, signals, etc.). As the capacity utilization of HSR infrastructure increases, so do the maintenance requirements. Hence, the operations and maintenance functions must be effectively integrated. In Japan, the HSR assets are owned by the operator, making it the operator’s responsibility to maintain the assets appropriately. In the Republic of Korea, on the other hand, the government owns the assets, and the operator carries out maintenance under a special contract. In such an arrangement, the coordination between the various agencies responsible for the operations and for maintenance, respectively, is essential and must be considered in HSR implementation elsewhere.

The same focus given to technology must also be given to human resources (HR) development within the HSR organization. People are an essential component of the railway system, and human error can also jeopardize safety. In Japan, there is an acute focus on HR development through regular on-the-job training, group training, and self-improvement.

The third message relates to the continuous improvement of existing practices. Any system degrades over time. Hence, all stakeholders must make continuous efforts to improve the current system. In both Japan and the Republic of Korea, technology and HR training methods have continuously evolved. More importantly, the safety regulations in these countries have also been upgraded from time to time: the Republic of Korea amended its Railway Safety Act in 2004 and Japan revised its Railway Business Act in 1986. Both countries clearly mandate implementing plan–do–check–act (PDCA) cycles for maintenance and HR development.

Moreover, various parts of the system should evolve in sync with each other. For example, over the years, the railway standards in Japan have changed from being specification based (where standards provide detailed specifications for each item on what to do) to now being performance based (where the performance criterion specifies what needs to be achieved but leaves how to do it to the operator). This shift occurred mainly to avoid the problem of specifications often not being able to keep up with the pace of technical improvements.

As to the relevance of systems thinking in the context of railway safety in India, the country’s railway accident figures suggest that the lessons are directly applicable to India. Indeed, the recent actions by Indian Railways of introducing new technology and eliminating maintenance backlogs are steps in the right direction. Of the 29,419 incidents reported in 2015, 859 were due to mechanical defects, 93 due to signaling error, and 641 due to driver error. However, more than 95% of the accidents were classified as “others,” implying that focus must be placed with urgency on identifying the causes in detail considering the principles of systems thinking. Using cutting-edge technology is a sure move towards safety. However, the importance of capacity building for employees and effective organizational coordination prioritizing safety cannot be downplayed. The recent accidents involving the Boeing 737 MAX, where the limits of software development were pushed without due consideration to its effect on safety because of inadequate multistakeholder consultation within the organization, clearly demonstrate that even the safest modes of transportation are susceptible to failure if systems thinking is not adopted.

The upcoming Mumbai–Ahmedabad HSR in India thus presents a unique opportunity to inculcate the principles of systems thinking in HSR and railway safety. The highest priority in the country is for the stakeholders to collaborate and conduct India-centric research on developing harmonized safety standards, to identify challenges in implementing them, and to thoroughly learn from past accidents to further improve the system.

Comments are closed.