In the eyes of many commentators, the US dollar’s reign as the global reserve currency is under threat from two angles. The first comes from within the US—a permanent deficiency in demand or secular stagnation; and the second from the People’s Republic of China (PRC), and in particular from a fully convertible yuan. In a recent seminar tour, which covered the Asia and the US, including the Asian Development Bank Institute, we spelled out why these fears are overdone. Far from being in decline, the US is in the ascendancy in our view. We summarize these arguments here.

Reserve currency status is worth $

The US has and continues to benefit greatly from its reserve currency status. Official data show that the dollar was involved in more than 85% of all currency transactions last year. More than 60% of global reserves—which have quadrupled in size since 2000 largely due to PRC and Japanese acquisitions—are held in dollars. The quid pro quo is: manage your currency well, maintain its store of value and we will pay you seigniorage to hold it as a reserve asset. Seigniorage benefits are significant—for example, the US has enjoyed a higher rate of return on its assets held abroad than it has had to pay foreigners on their dollar assets every single quarter since 1960—defying the law of one price. It is not a prize to be given up lightly.

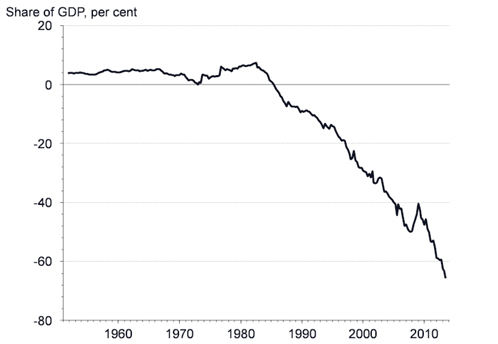

But the dollar has been in secular decline, arguably since the end of Bretton Woods— it is worth less than half its value in 1973, in real terms. The US has run persistent current account deficits, meaning that its net investment position is some 60% of US GDP in the red—an extraordinary fact. And the past few decades have seen a succession of asset price booms and busts. Just bad luck or as some, notably former US Treasury Secretary Larry Summers argue, a reflection of a broader secular stagnation: a persistent deficiency in demand that monetary policy cannot solve, leaving it aimlessly pushing on string, igniting one asset price bubble after another. In effect, Summers argues, the US needs seriously negative interest rates. Such a prognosis hardly bodes well for the world’s reserve currency. Meanwhile, the PRC continues its rise—it is probably already the world’s largest trading nation—and to gradually liberalize, the People’s Bank of China’s decision to widen its RMB monitoring bands is another step toward a fully convertible yuan. Would that be the final nail in the dollar’s coffin, or a blessing in disguise?

US net external assets

Share of GDP, percent

Source: Thomson Reuters Datastream / Fathom Consulting

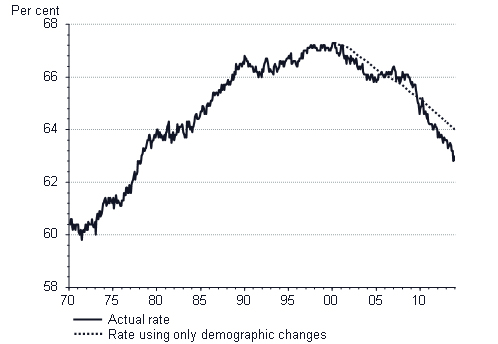

We start by refuting the idea that the US is in secular stagnation, let alone decline. While the labor market recovery does appear weaker than usual, there is no structural problem. The labor participation rate has fallen sharply since 2000, but most of that is simply demographics (see chart below, the dotted line is what we estimate would have happened to US participation purely because of demographics). Moreover, despite this decline the US still has the highest participation rate among the major developed economies. And if we look just at private sector job creation (arguably the more important metric) we see a very robust recovery—private payrolls are nearly 8% above their pre-crisis peak.

US participation rate

Percent

Source: Thomson Reuters Datastream / Fathom Consulting

This is because, in our view, the US has used the time afforded it by quantitative easing to fix the underlying problem—the banks. It has also cleared its housing and labor markets. As a consequence, its productivity performance in the current recovery is bang in line with the average post-war experience, in both trend and levels. This makes the US virtually unique among its peers, including the PRC, and argues strongly in favor of it retaining its reserve currency status, and that the US needs a strongly positive real neutral rate of interest.

But what of the threat posed by the PRC? What does it take to be the reserve currency? Theory lists five key factors: economic size; a well-developed financial system; confidence in the currency’s value; political stability; and network externalities. The last of these factors more or less guarantees that there can only be one reserve currency at a time; but there is no reason why international investors might not want to hold a basket of currencies as a store of value, or to price different commodities in different currencies for example. The PRC does or will very soon fulfill the first category, and as we note above the dollar has seriously undermined confidence in its long-run value. But the PRC is a very long way from being able to satisfy the other necessary conditions. When we look at how the dollar overtook sterling we find that size is important, but not very. The US became the world’s largest economy in 1880, but the dollar did not overtake sterling conclusively until the late 1950s. The key development was the establishment of the Federal Reserve in 1913, and a viable banking and financial system. So, the PRC has the size, but not the means to be the reserve currency. Moreover, it is unlikely to have what is needed for decades yet, even if everything goes well. And that is a very big if—first the PRC has to achieve what very few other countries have managed and escape the middle-income trap. That will require the PRC to not just catch up with but move the technological frontier forward. What is clear is that it is in everyone’s interest that it succeed, including the US.

It’s all in the game

The US and the PRC interaction can be thought of as a “game,” the solution to which can be cooperative or uncooperative. They are both large, open economies: they each have market power—their choices influence market prices. Consequently, their choices can generate multiple equilibria for themselves and for the global economy.

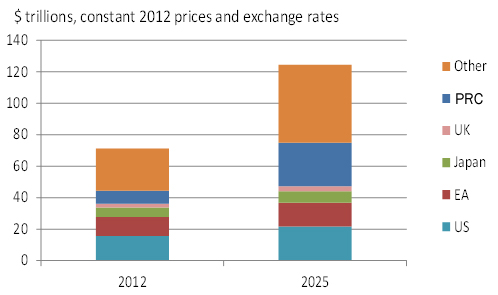

Cooperative outcome: the PRC spends much more and the US stops the prints press—global rebalancing. The PRC takes the reins of the global economy, and pulls it toward sustained recovery—ends the “demand deficit.” The next two decades will look like the two decades after the global recession of the early 1980s, with world growth over 5% per annum, global GDP doubles by 2025. But, the PRC will be ahead of the US even on a per capita basis and the yuan will become a key player in the reserves basket—but not the reserve currency.

Global GDP

$ trillions, constant 2012 prices and exchange rates

Source: Fathom Consulting

Uncooperative outcome: the PRC saves more and because it has not developed a viable financial system it is forced to send those savings abroad. Meanwhile, the US and the rest of the developed world are incapable of generating the demand needed to mop up the PRC’s existing excess supply. Deflation and an endless series of asset price bubbles beckon as central banks do what they can to try and weaken their currencies. It is more like the 1930s than the 1980s.

A fully convertible yuan is a necessary first step toward achieving the first or cooperative outcome, and to putting the PRC and the rest of the world on the path to prosperity. A fully open capital account and a functioning, viable financial system are also necessary conditions.

Comments are closed.