As the economy is a gendered structure, trade liberalization affects women and men differently in various dimensions and through different channels. Trade liberalization causes structural transformation in terms of production and, therefore, leads to changes in employment patterns and income. However, the effect of trade is heterogenous across different sectors. While some sectors may benefit from liberalization and experience an expansion, e.g., export-oriented production, others may lose from trade and suffer from a contraction, e.g., import-competing production. As women are traditionally concentrated in only a few specific occupations and sectors, women do not equally gain from liberalization as much as men do. To conduct a gender-aware analysis, it is important to acknowledge that women play multiple roles in the economy, such as workers, producers, traders, consumers, and taxpayers, and are entitled to public services. This article analyzes the impact of trade on women’s employment in the Thai labor market by focusing on women as workers and producers in the agriculture and manufacturing sectors.

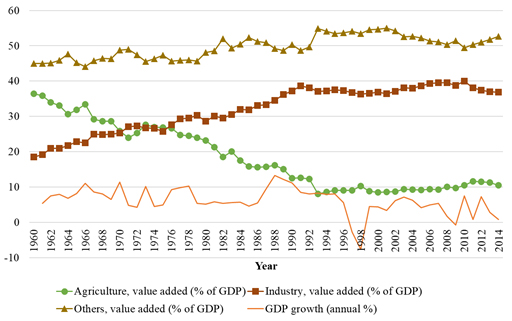

In the 1970s, Thailand went through structural transformation in terms of its export and import patterns by liberalizing its trade and adopting an export production strategy. Thailand changed from being an agricultural produce exporter, such as of rice, to becoming a manufactured goods exporter, starting with garments and parts and components (Figure 1). In parallel, Thailand transitioned from a primitive, agriculture-based economy to a newly industrialized economy. From 1971, the share of manufacturing outweighed that of agriculture and became even more important from the 1980s onward (Korwatanasakul 2019). Like other countries, in Thailand, the manufacturing and services sectors grew significantly faster than the agriculture sector. This has had several implications on women’s employment in different sectors.

Figure 1: Structural transformation, 1960–2014

GDP = gross domestic product, LCU = local currency unit.

Note: Agriculture, industry, and others are expressed in net output as percentages of GDP.

Source: Author, based on data from the World Bank’s World Development Indicators for 1960–2014.

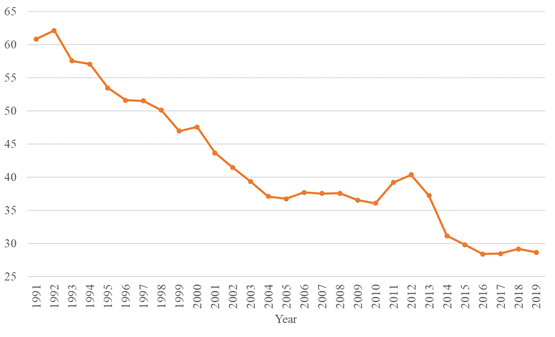

Even though there is no direct evidence regarding the impact of trade and women’s employment in the agriculture sector, comparing the trends of trade liberalization and employment in the labor market may provide some insights. According to the World Bank (2020a), estimated female employment in agriculture in Thailand as a share of female employment declined from 60.8% in 1991 to 27.6% in 2019 (Figure 2). As previously discussed, the agriculture sector has been growing slower than the other two sectors since 1971. This slower growth caused a shift of labor to the manufacturing and services sectors. Looking at the role of women in the agriculture sector, a recent study by Akter et al. (2017) found that Thai women play an active role in agricultural groups, have equal access to productive resources, and have greater control over household income than men. Despite the positive trend, the majority of women (53% of female workers in the agriculture sector) are considered as unpaid family workers1 (National Statistical Office 2019). On the contrary, own-account workers comprise 63% of male workers in the same sector. Furthermore, 5.2 million women, as opposed to 300,000 men, are classified as persons not in the labor force because they mainly engage in non-market activities (also known as “unpaid care work”). Apart from household chores, they may also help their families with activities directly and indirectly related to farming, such as collecting water. Women who are unpaid family workers or those who mainly spend time on non-market activities without pay on a farm owned or operated by the household head or any other member would benefit less than men in the case of agricultural trade expansion, whereas they would be hit harder in the case of agricultural trade contraction. Therefore, women are relatively more vulnerable than men in this sector.

Figure 2: Female employment in agriculture (% of female employment)

Note: Employment is defined as persons of working age who were engaged in any activity to produce goods or provide services for pay or profit, whether at work during the reference period or not at work due to temporary absence from a job, or to a working-time arrangement. The agriculture sector consists of activities in agriculture, hunting, forestry, and fishing, in accordance with division 1 (ISIC 2) or categories A-B (ISIC 3) or category A (ISIC 4).

Source: Author, based on data from the World Bank’s World Development Indicators for 1991–2019.

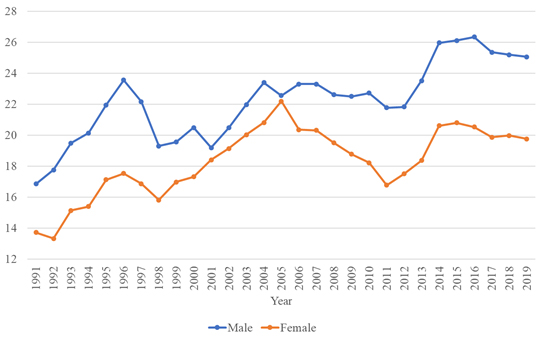

In terms of the manufacturing sector, like other developing countries, Thailand has also experienced the feminization of employment through export orientation. Female employment gains in manufacturing employment have been particularly strong in Thailand. In 1991, the estimated female employment in industry as a share of female employment was 13.7%, while the share increased to 20% in 2019 (World Bank, 2020a) (Figure 3). This corresponds to the downward trend of female employment in the agriculture sector from which female workers have been moving away. Korwatanasakul, Baek, and Majoe (2020) found that trade promotes inclusive job creation and provides more job opportunities for rural, female, and low-skilled workers. Despite the female employment gains, horizontal gender segregation as well as vertical gender segregation are observed in the manufacturing sector, where women are concentrated in the garments and textiles industries and in clerk and elementary positions (National Statistics Office 2019). These industries and positions are generally labor-intensive, low value added, unproductive, and low-paid—in other words, these positions are easily replaceable. Thus, in times of crisis, it is more likely that women will be the first group of workers to be laid off. In fact, the recent impacts of the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) are estimated to hit women harder than men (United Nations 2020; World Bank 2020b), leaving women with lower income, greater unemployment, and limited access to social security and stimulus packages by the Thai government (Ketunuti and Chittangwong 2020).

On the other hand, men are distributed more evenly across industries and placed in more secure technical and professional positions. Figure 3 shows that while male employment in the manufacturing sector dropped on average 1 percentage point after the financial crisis in 2007, female employment experienced a sharp drop from 20.2% to 16.8% (approximately 4 percentage points) during the same period. With the existing industrial and occupational segregation, women are more vulnerable than men and therefore may not fully enjoy the benefits of trade liberalization.

Figure 3: Share of total male/female employment in manufacturing (%)

Note: Employment is defined as persons of working age who were engaged in any activity to produce goods or provide services for pay or profit, whether at work during the reference period or not at work due to temporary absence from a job, or to a working-time arrangement. The industry sector consists of mining and quarrying, manufacturing, construction, and public utilities (electricity, gas, and water), in accordance with divisions 2-5 (ISIC 2) or categories C-F (ISIC 3) or categories B-F (ISIC 4).

Source: Author, based on data from the World Bank’s World Development Indicators for 1991–2019.

In conclusion, in the case of Thailand, trade liberalization affects women and men differently in both the agriculture and manufacturing sectors. In contrast with men, women are horizontally and vertically segregated into certain occupations and positions with higher vulnerability and less benefit from trade. To promote gender equality in our economies and society, it is therefore crucial for all stakeholders, especially policymakers, to recognize our economy as a gendered structure and to mainstream gender into trade policies and other economic and social policies as well.

_____

1 According to the Thai Labour Force Survey (National Statistics Office 2019), unpaid family workers are classified as persons in the labor force, while persons who mainly engage in non-market activities or reproduction are classified as persons not in the labor force.

References:

Akter, S., P. Rutsaert, J. Luis, Nyo Me Htwe, Su Su San, B. Raharjo, and A. Pustika. 2017. Women’s Empowerment and Gender Equity in Agriculture: A Different Perspective from Southeast Asia. Food Policy, 69 (May): 270–279.

Ketunuti, V., and S. Chittangwong. 2020. Against the Odds: Stories from women in Thailand during COVID19.

Korwatanasakul, U. 2019. Global Value Chains in ASEAN: Thailand, ASEAN-Japan Centre Paper 10. Tokyo: ASEAN-Japan Centre.

Korwatanasakul, U., Y. Baek, and A. Majoe. 2020. Analysis of Global Value Chain Participation and the Labour Market in Thailand: A Micro-Level Analysis, ERIA Discussion Paper 331. Jakarta: ERIA.

National Statistical Office. 2019. The Labor Force Survey, National Statistical Office Quarter 4: October-December 2019.

United Nations. 2020. Policy Brief: The Impact of COVID-19 on Women.

World Bank. 2020a. World bank open data [Data file]. Washington, DC: World Bank.

World Bank. 2020b. Gender Dimensions of the COVID-19 Pandemic (Policy Note).

Comments are closed.