In 2015, the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) and the People’s Republic of China (PRC) signed an Upgrade Protocol to improve the original Framework Agreement for the ASEAN-People’s Republic of China Free Trade Area (ACFTA) as well as their Agreement on Trade in Goods, Services, and Investment. The Upgrade Protocol entered into force in July 2016, and implementation will start from August 2019.

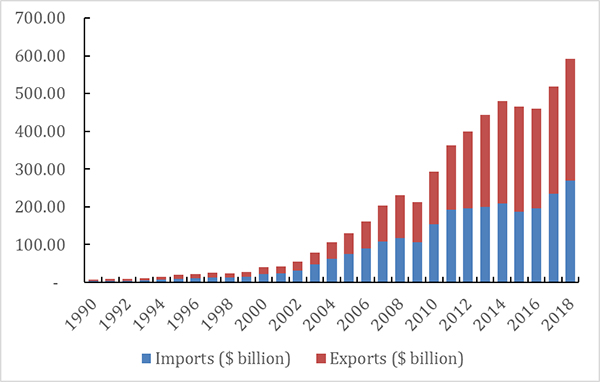

Since the ACFTA was launched, the PRC’s share of ASEAN’s total merchandise trade increased from 8% in 2004 to 21% in 2018, making it ASEAN’s biggest trading partner with trade amounting to US$591.1 billion (Figure 1). The PRC also rose to become the third-largest source of foreign direct investment in 2017, with investment flows amounting to US$11.3 billion.

Figure 1: ASEAN-PRC Trade, 1990–2018

Source: Asia Regional Integration Center database, Asian Development Bank.

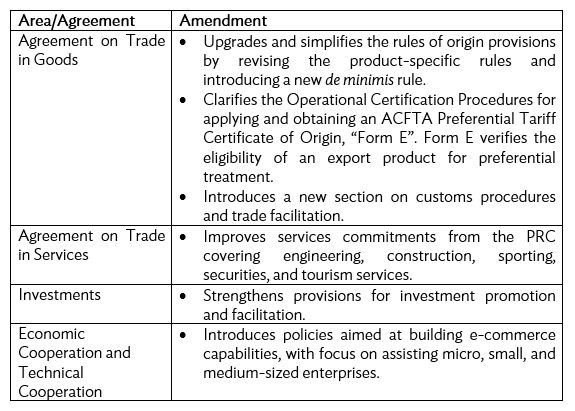

But how will upgrading the agreement likely affect trade and investment between ASEAN and the PRC? The key amendments of the ACFTA involve simplifying rules of origin, improving commitments from the PRC in critical services sectors, and implementing policies to strengthen investment flows and e-commerce.

Table 1: Key Amendments Introduced by the ACFTA Upgrade Protocol

Sources: Protocol to Amend the Framework Agreement on Comprehensive Economic Cooperation and Certain Agreements between ASEAN and the People’s Republic of China; Ministry of Trade and Industry, Singapore. 2016. Guide to the Upgraded ASEAN-China Free Trade Area (ACFTA).

Interestingly, the Upgrade Protocol does not do much to address non-tariff barriers, despite firm-level surveys suggesting that they continue to grow and suppress trade (Ing, 2016). Even for tariffs, studies point to low utilization rates for ACFTA tariff concessions (Tham and Yi, 2015). If low utilization rates are mainly due to difficulties in complying with rules of origin, for instance, upgrading the agreement could significantly increase trade flows by simplifying such rules. But if low utilization rates are mainly the result of low margins of preference, or the difference between most-favored-nation and ACFTA preferential tariffs, the likely impacts of an upgraded ACTFA will be more complex.

Margins of preference are likely to be low, or even zero, for trade in parts, components, and other intermediate goods because of various tariff exemption schemes. The WTO Information Technology Agreement, for example, provides duty exemptions for trade in electronic parts and components that dominate supply chains in Southeast and East Asia, even for countries that are not signatories.

For trade in other types of parts and components, various duty-drawback schemes like bonded warehouses or the location of multinationals in duty-exempt export processing zones also make these tariff preferences redundant. Even if this were not the case, it is very difficult to design rules of origin for supply chain-driven trade, which by its nature involves limited value-addition or transformation (Athukorala and Kohpaiboon, 2011). Therefore, the simplification of rules of origin and other related reforms in the upgraded ACFTA are likely to affect trade in final rather than intermediate goods, constituting a much smaller share of ASEAN-PRC trade. This change would also aggravate the ASEAN-PRC trade imbalance.

That said, improvements to the ASEAN-PRC agreement on trade in services have the potential to significantly strengthen trade relations given the sector’s high growth potential and persistent market barriers and the implications of trade challenges between the United States (US) and the PRC.

The trade dispute between the PRC and the US has already affected supply chains, with investment being diverted away from the PRC and toward some ASEAN countries. The strengthening of provisions that promote or facilitate investment between the PRC and ASEAN could increase flows from the former to the latter to avoid punitive tariffs, especially if the US-PRC trade dispute is viewed as more than transitory. Even if the dispute is resolved soon, the restructuring may continue in order to diversify risk. Unless there are major domino effects, this restructuring could be a defining legacy of US-PRC trade tensions, similar to the spread of Japanese investments in the region after the Plaza Accord in 1985.

All of this assumes that the ASEAN-PRC agreements are implemented faithfully. This is no easy task when considering that domestic laws may need to be amended to accommodate these new accords.

Ever since the ACFTA was first proposed, there has been concern over the possible negative impacts on production and employment in sensitive sectors in ASEAN countries. Indonesian producers, for instance, requested a delay in the implementation of the original ACFTA tariff reductions for some 228 items, without success.

Although some of these fears may have since subsided, they have not been eliminated. For example, there have been delays in the enactment of national laws and regulations to implement the Upgrade Protocol. Domestic industry groups continue to push for protection, and some wield significant influence over governments in the region. In this environment, the flexibility that characterizes ASEAN cooperation and institutional arrangements could hand members a convenient pretext for non-compliance. How to enforce the ASEAN-PRC accords remains an issue.

If implementation issues can be overcome, these amendments, together with the new provisions on customs procedures and trade facilitation, present new opportunities for further increasing ASEAN-PRC trade. It is more important now than ever that the upgraded ACFTA succeed given the growing uncertainty relating to the rules that govern global trade and commerce and the threat this uncertainty poses to future growth and stability in the region.

_____

References

Athukorala, P. and A. Kohpaiboon. 2011. Australian–Thai Trade: Has the Free Trade Agreement Made a Difference? Australian Economic Review, 44(4): 457–467.

Ing, L. Y. 2016. Non-Tariff Measures in ASEAN. Economic Research Institute for ASEAN and East Asia: Jakarta.

Menon, J. 2018. “Can FTAS Support the growth and spread of Global Production Networks”, in J. Menon and T.N. Srinivasan (eds.) Integrating South and East Asia: Economics of Regional Cooperation and Development. Oxford: Oxford University Press: 59–92.

Tham, S. Y. and A. Yi. 2014. Re-examining the Impact of ACFTA on ASEAN’s Exports of Manufactured Goods to China. Asian Economic Papers, 13(3): 63–82.

Comments are closed.