The notion of a middle-income trap has generated much interest and discussion, but little consensus. There is no agreement on what the trap is or how long a country needs to be at the middle-income stage to be considered trapped. Much of the current discussion is about growth slowdowns, but is a slowdown the same as a trap? It is also possible that the trap does exist but we do not know what causes it.

What we do know is that nearly half of the economies in the world today are at the middle-income stage—105 of 214. The others are low income (34) or high income (75). The large number of middle-income economies may not be surprising given that the middle-income range, as defined by the World Bank, is wide and stretches from about $1,000 to nearly $13,000 in gross national income per capita. Some countries have only recently graduated from the low-income stage, such as India in 2007, and others may graduate to high income before the end of the decade, such as Brazil or Turkey. These countries are not likely to be trapped or will soon be released from the trap. However, there are a sizeable number of economies that are still middle income and have been so for the past 50 years or more. It is natural to think these economies are stuck and suffer from a common pathology.

A growth slowdown, as expected

It is not surprising that middle-income countries would experience a growth slowdown as they move up the growth ladder. It is in fact implied by a fundamental idea of economics. When capital (e.g., plant, machinery, infrastructure or human capital) is scarce, additions to capital generate high returns. Poor economies with low capital accumulation would naturally generate higher returns and result in higher growth. As a country moves through the middle-income phase and accumulates more capital, its growth rate would decline. A middle-income slowdown, although not necessarily a trap, may be explained by this process. In the same way, a runner who slows his pace near the end of a race will take longer to cross the finish line.

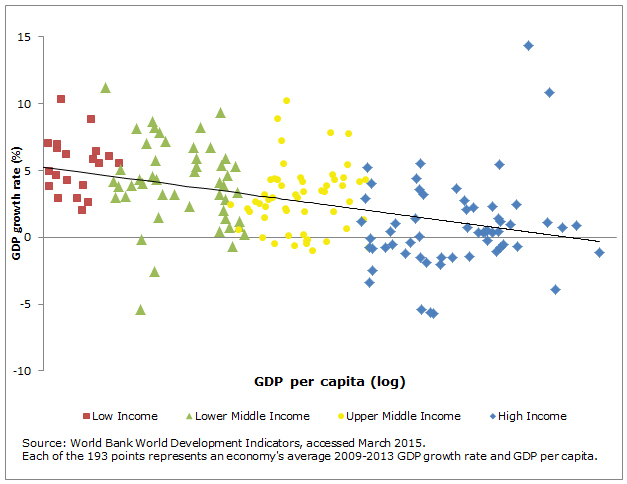

A review of recent growth rates around the globe does support such an inverse relationship between the level of development and the growth rate. In the 5 years to 2013, the world’s low-income economies grew at an average annual rate of 5.2%, whereas lower-middle-income countries grew at 4.0%, upper-middle-income countries at 2.9%, and high-income countries at 0.7%.1

A problem of wages and value added

However, those who devised the notion of a “middle-income trap” had more in mind than a growth slowdown (Gill and Kharas 2007). They focused on the nature of production and the relationship between wages and the value of output. An economy makes an initial transition from low to middle income through a structural transition from agriculture to industry, where productivity and returns are higher. In this first stage, enterprises make low-value goods on the lower rungs of the industrialization ladder by producing garments, processing food, and churning out household goods using simple or mature technology processes on wood, metals, and plastics. The output can be priced and sold competitively because industrial wages are low. As wages rise, a country loses competitiveness in these goods and yet cannot make the transition to higher value, more technologically sophisticated goods (and services) that support higher wages. The economy gets trapped between low-value and high-value production segments. Whether this actually happens and explains growth slowdown is unknown, because it has not been adequately tested.

Defining a group of potentially trapped economies

Nonetheless, our recent paper does lend support to this idea that the value and sophistication of production may help to explain what lies behind the middle-income trap or related slowdowns (Vandenberg, Poot, and Miyamoto 2015). We looked beyond growth rates and compared high- and middle-income economies across a range of development variables. To create the country groups, we started with the 200 plus economies in the world and eliminated those with a population of less than 3 million and those whose incomes are derived heavily from petroleum exports. We then eliminated all low-income countries and also all middle-income countries that had been at the low-income stage in any year since 1987, the year the World Bank began classifying countries into income groups. This process excluded the People’s Republic of China from our analysis as it was still a low-income country in the mid-1990s.

This left us with 59 economies, of which 35 are high income. The other 24 are middle income and have been so since 1987, a period of just over 25 years. We further extrapolated the 1987 thresholds back to 1961 and found that all these economies for which there were data back to that year were middle income throughout. Thus, they were middle income for a period of over 50 years. In all other cases, the countries were middle income from at least as far back as we had data (some from at least the late 1960s, some from the 1970s, etc.). By this method we arrived at a group of countries that might possibly be stuck in a middle-income trap. We then tested for differences between the high- and middle-income groups across 10 categories of variables.

Comparing high- and middle-income groups

We found that compared to the middle-income countries, the high-income economies had significantly higher levels of expenditure on research and development, higher numbers of patent and design registrations, a greater quantity and higher quality of transport and energy infrastructure, and higher quality education. All of these factors would support the notion that higher productivity and technology use and the production of higher value goods and services are important in differentiating high-income economies from middle-income ones.

The gap between the income groups was also pronounced for governance indicators. In addition, a gradation exists within the middle-income group: the wealthier middle-income economies exhibit better governance than their less wealthy counterparts. This result accords with expectations that transparent and stable government is essential for supporting investment, trade, and economic exchange. Likewise, the most prosperous middle-income countries tend to exhibit better developed and more reliable infrastructure, traits that are shared universally at the high-income level.

Income inequality offers another striking distinction. The middle-income group includes many economies with high levels of inequality. A more equitable distribution of income is a potential indicator of better human capital as the population would enjoy more security and professional mobility. The distinction between the high- and middle-income groups is less obvious in some of the other categories that we examined. In terms of financial sector development, for example, middle-income economies as a group demonstrate considerable strength.

Conclusion

The debate about whether a middle-income trap exists or whether it is an expected growth slowdown will continue. Meanwhile, it may be best to focus on the particular challenges facing middle-income countries and the appropriate policy measures. In this regard, it may be better to speak of a middle-income transition and focus on the factors that are associated with high-income economies and movement up the production value chain.

Economic Growth and Income Per Capita, 2009-2013

_____

1 The figures are based on average annual gross domestic product growth rates for 193 economies for 2009–2013. For a few countries, data covered less than 5 years.

References:

Gill, I. and H. Kharas. 2007. An East Asian Renaissance: Ideas for Economic Growth. Washington, DC: World Bank.

Vandenberg, P., L. Poot, and J. Miyamoto. 2015. The Middle-Income Transition around the Globe: Characteristics of Graduation and Slowdown. ADBI Working Paper 518. Tokyo: Asian Development Bank Institute.

Photo: By Steve Evans (“Woman from Tajikistan with stroller“). Licensed under Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic via Wikimedia Commons.

Comments are closed.