Thanks to its sustained economic growth over the last several decades, Asia has become the world’s most dynamic region. Maintaining this impressive growth rate, however, requires market integration to ensure the free flow of goods, services, and capital across borders (ADB 2013). Indeed, interplay of market forces and increased participation in trade have been decisive in the growth of emerging Asian economies. Until now, most of Asia’s final goods have been exported to Europe and the United States. Access to large markets allowed Asian countries to exploit their economies of scale on the one hand, and stimulate growth in their productive sectors on the other. With the rise of Asia, it is time for these countries to cooperate and become an integrated market of their own.

Thanks to its sustained economic growth over the last several decades, Asia has become the world’s most dynamic region. Maintaining this impressive growth rate, however, requires market integration to ensure the free flow of goods, services, and capital across borders (ADB 2013). Indeed, interplay of market forces and increased participation in trade have been decisive in the growth of emerging Asian economies. Until now, most of Asia’s final goods have been exported to Europe and the United States. Access to large markets allowed Asian countries to exploit their economies of scale on the one hand, and stimulate growth in their productive sectors on the other. With the rise of Asia, it is time for these countries to cooperate and become an integrated market of their own.

Enhancing South Asia market integration

Like elsewhere in the world, market consolidation through trading arrangements is growing rapidly in Asia. In East Asia’s export-oriented industries, market-led de facto regionalization preceded formal de jure integration. South Asian economies, on the contrary, have been unable to gear up market integration either formally or informally, and the subregion has remained the least integrated, although its geography and comparative advantages hold the potential for a highly integrated trade, investment, and production space (Tewari 2008).

Skeptics have long been doubtful about the potential of a subregional economic grouping among South Asian nations due to the subregion’s sluggish economic activities prior to the 1970s and poor performance in international trade. Import-substituting policies, along with restrictive trade and industrial rules constrained these economies’ subregional and global trade expansion for a long time. In fact, economic integration under the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC) regime was not explicitly envisaged until as late as the 1990s.

Since the early 1990s, however, several attempts have been initiated to boost South Asian economic integration through a number of trade pacts at the bilateral, subregional, and plurilateral levels. As the umbrella organization in South Asia, SAARC has taken initiatives to enhance integration—the South Asian Preferential Trading Arrangement (SAPTA) and the South Asian Free Trade Area (SAFTA), and more recently the SAARC Agreement on Trade in Services (SATIS), which was signed in 2010 (SAARC Secretariat 2004, 2010).

Little has been achieved under these instruments, and barring Afghanistan and Nepal, all the South Asian economies depend heavily on markets outside the region as their export destination. However, this does not mean that intra-subregional trade has declined. Indeed South Asia’s trade with both its subregional and external partners has increased significantly since 1990s, although trade growth with external partners has been faster.

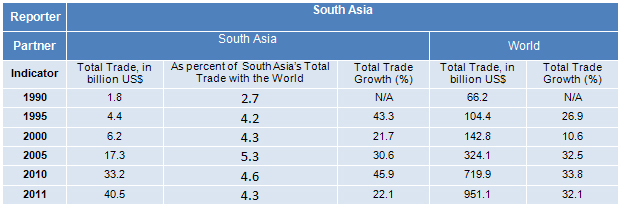

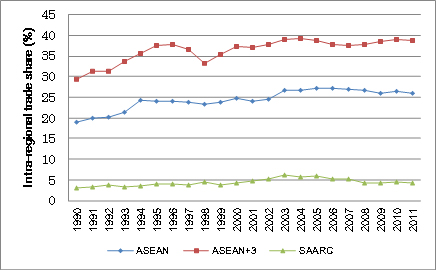

Statistical evidence suggests that intra-subregional trade among SAFTA members is rising slowly and steadily. As indicated in Table 1, South Asia’s intra-subregional trade share increased from 2.7% in 1990 to 4.3% in 2011. Also, Figure 1 provides a comparative picture of intra-subregional trade shares for the member states of SAARC, the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), and ASEAN+3. It clearly shows that SAARC largely trails the other two in terms of subregional integration. For example, in 2011, SAARC’s intra-subregional trade was only 4.3%, whereas the corresponding figures for ASEAN and ASEAN+3 were 26% and 39%, respectively. SAARC’s share is still very low when compared with corresponding figures from other regions, but the positive trend is clear. As such, policymakers and business communities in South Asia have become increasingly interested in economic integration in South Asia and the potential benefits that may come along with it.

Table 1: South Asia’s total trade within the subregion and with the world

Source: Asia Regional Integration Center (ARIC) Integration Indicators Database. Available: http://aric.adb.org/indicator.php, accessed 20 August 2012.

Figure 1: Intra-regional trade within SAARC, ASEAN, and ASEAN+3

Source: Asia Regional Integration Center (ARIC) Integration Indicators Database. Available: http://aric.adb.org/indicator.php, accessed 20 August 2012.

ASEAN: Association of Southeast Asian Nations, SAARC: South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation

A recent Asian Development Bank Institute working paper (Moinuddin 2013) focuses on the promises that sub-regional economic integration in South Asia hold. The paper observes that the structure of economies in South Asian countries has changed since the 1970s, when agriculture was the predominant sector in South Asia in terms of share in GDP. Since then, the services sector has grown rapidly and at present accounts for more than half the region’s economy. The manufacturing sector has remained rather weak and has been predominated by the textiles and clothing industry. With industry and agriculture performing below par, South Asia’s services sector is likely to become the harbinger of the region’s growth paradigm (Nabi et al. 2010).

SAFTA’s potential in accelerating intraregional trade

Several quantitative and qualitative studies have been conducted on SAPTA/SAFTA’s potential gains, but the findings have largely remained inconclusive. The critical empirical finding of Moinuddin (2013), which differs from some earlier works, is related to SAFTA’s potential for generating intra-subregional trade. The regression with country-pair panel data took into account the typical gravity variables as well as additional explanatory and dummy variables that were found to be relevant for investigating the effects of FTAs on trade flows. The relationship between the trading partners’ GDP and export flows was found to be more than proportional. This phenomenon, coupled with the impressive economic performance of South Asian countries in recent years, may lead the countries of this subregion to further enhance their trade flows. Moreover, an additional regression with overall trade restrictiveness indices has suggested that scaling down tariff and nontariff barriers will positively affect intra-bloc trade among South Asian economies. This calls for an effective implementation of SAFTA’s trade liberalization program. Against this backdrop, there are reasons for optimism about SAFTA becoming a cohesive and profitable regional trading bloc. South Asian economies, which typically maintain high trade restrictions, will benefit from improved subregional and global integration by reducing trade barriers.

The recently signed SAARC Agreement on Trade in Services entered into force in late 2012, but it is yet to be fully implemented. To reap the benefits of economic integration, the subregion needs to promote liberalization in the services sector, a promising area for a rising South Asia. Additionally, an intra-SAARC investment agreement is likely to create an enabling environment for cooperation beyond mere trade to include investment and finance, among others (SACEPS 2002, Raihan 2012).

Paving the way for South Asia’s global integration

By maintaining the primacy of economic integration, countries of the subregion can expect effective cooperation and integration in South Asia. At the end of the day, SAFTA’s success will be assessed in terms of its trade generating capacities. The potential is already there; it is now a matter of effective implementation of the trade deal. This will entail South Asian countries addressing not only economic factors such as trade facilitation and infrastructure development, but also some non-economic factors like creating political will and building confidence. For this, South Asian economies must conceptualize integration as an evolving process. Indeed, this is reflected in SAARC, which has an explicit intent to move in the direction of an economic union. The growth of the South Asian countries offers prospects and challenges for deeper integration with the global economy, and integration under SAFTA is the first step in that direction.

References:

ADB. 2013. Regional Cooperation and Integration in a Changing World. Manila: ADB. Moinuddin, M. 2013. Fulfilling the Promises of South Asian Integration: A Gravity Estimation. ADBI Working Paper Series. No. 415. Tokyo: Asian Development Bank Institute.

Nabi, I. et al. 2010. Economic Growth and Structural Change in South Asia: Miracle or Mirage? International Growth Center Working Paper 10/0859. London: International Growth Centre.

Raihan, S. 2012. SAFTA and the South Asian Countries: Quantitative Assessments of Potential Implications. Munich Persona RePEc Archive (MPRA) Paper. No. 37884. Munich: Munich Personal RePEc Archive.

SAARC Secretariat. 2004. Agreement on South Asian Free Trade Area (SAFTA). SAARC Secretariat: Islamabad.

SAARC Secretariat. 2010. SAARC Agreement on Trade in Services (SATIS). SAARC Secretariat: Thimphu. 29 April.

South Asia Center for Policy Studies (SACEPS). 2002. SACEPS Task Force Report on South Asian Investment Cooperation. Dhaka, Bangladesh: SACEPS.

Tewari, M. 2008. Deepening Intraregional Trade and Investment in South Asia: The Case of the Textiles and Clothing Industry. ICRIER Working Paper. No. 213. April.

Comments are closed.