Dietary diversity refers to the variety of foods and food groups consumed within a diet, encompassing different nutritional sources. Across Asia, dietary diversity is exemplified by a distinctive range of food practices and culinary innovations. This includes staples such as rice and noodles, animal-sourced foods, including pork and lamb, plant-based proteins like legumes and tofu, and various vegetables, fruits, and spices. Rice, for example, is the cornerstone of Asian diets and is ubiquitous across the region. Its versatility enables it to be transformed into numerous forms, reflecting local innovations, such as rice noodles (a staple in Southeast Asia), dosa (a fermented rice and lentil crepe popular in India), and rice wine (variants such as Chinese huangjiu, Japanese sake, and Korean makgeolli).

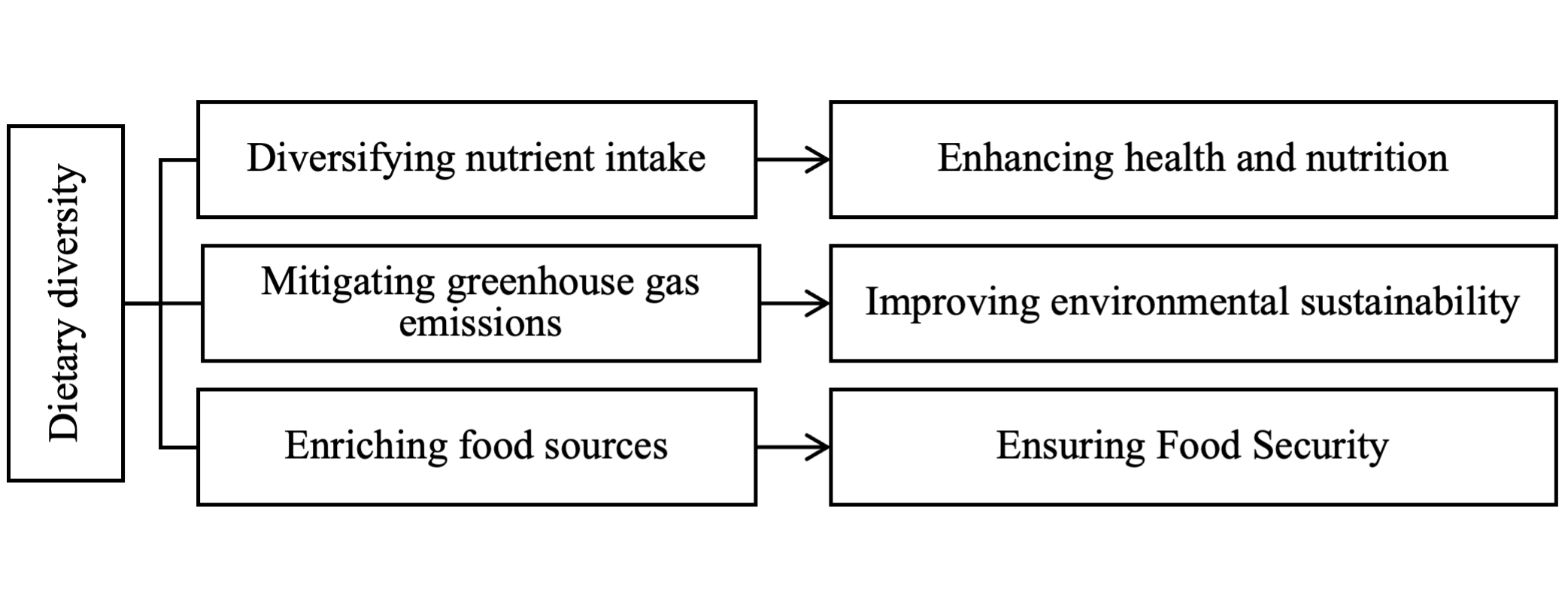

A diversified diet goes beyond merely satisfying the palate and stomach. It is pivotal in enhancing human health and nutrition, improving environmental sustainability, and ensuring food security (Figure 1). Miyamoto et al. (2019) analyzed 137 countries and highlighted that Japan demonstrated the second-highest dietary diversity scores globally, aligning closely with its globally leading life expectancy.

These benefits are particularly salient in post-pandemic Asia, where the interplay between nutrition, ecological resilience, and societal well-being has gained heightened attention (Carrasco and Zhang 2022). Despite a relatively lower estimated proportion of the population facing hunger in Asia (8.1%) than in Africa (20.4%), Asia is home to over half of the world’s population suffering from hunger, amounting to approximately 385 million people—significantly higher than Africa’s 300 million (FAO 2024).

Figure 1: Dietary Diversity Impacts on Health and Nutrition, the Environment, and Food Security

Source: Authors.

Enhancing Health and Nutrition

In Asia, dietary patterns emphasize plant-based diversity, incorporating food types such as rice, noodles, vegetables, legumes, and tea. This dietary approach has been linked to improved health outcomes, including lower risks of total mortality and cardiovascular disease-related deaths (Baden et al. 2019). Tea, particularly green and black, is a cornerstone of Asian dietary culture. Countries such as the People’s Republic of China (PRC), Japan, Sri Lanka, and India are leading tea consumers, with daily consumption deeply embedded in social and cultural practices. Evidence suggests that among Chinese adults, daily consumption of green tea is associated with a reduced risk of developing type 2 diabetes and lower all-cause mortality in individuals already diagnosed with diabetes (Nie et al. 2021).

However, while dietary diversity offers significant health and nutrition benefits, it may also increase exposure to environmental chemicals. This arises because certain food items can act as primary sources of environmental contaminants, particularly in regions where agricultural or industrial practices lead to chemical accumulation in food chains. Yu et al. (2024) found that healthy dietary patterns, emphasizing diverse and nutrient-rich foods, were positively associated with plasma chemical exposure during pregnancy. These associations were notably stronger among Asian and Pacific Islander populations.

Improving Environmental Sustainability

The environmental impact of increasing meat consumption, particularly livestock meat, is another potential concern. Animal-sourced foods typically have significantly larger greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions and environmental footprints than plant-based alternatives (Qaim 2024). In contrast to typical Western diets characterized by high consumption of processed and red meats, the plant-based protein sources featured in traditional Asia diets, such as legumes, tofu, and lentils, provide essential nutrients and have a significantly lower carbon footprint. Recent estimates by Lucas et al. (2023) indicate that adopting a dietary shift away from animal-sourced foods could reduce annual monetized externalities, amounting to approximately $1,100 per capita in South Asia.

Dietary diversity in Asia offers the opportunity to simultaneously enhance nutrition and GHG emissions, demonstrating that these goals are not mutually exclusive but can be mutually reinforcing. According to Geyik et al. (2023), increasing the production and trade of nutrient-rich foods such as vegetables, eggs, and roots and tubers can effectively close nutrient gaps while minimizing emissions for most countries. Wang et al. (2022) emphasize that adjusting the dietary patterns of Chinese residents holds significant potential for reducing environmental pressures in the PRC.

Ensuring Food Security

Food security challenges persist across many Asian countries. In Bangladesh, significant shortfalls in producing non-staple crops, including pulses, vegetables, and fruits, hinder the availability of balanced diets (Ahmed et al. 2024). Similarly, the Lao People’s Democratic Republic continues to face severe malnutrition issues, with a stunting prevalence of 33% as of 2017 (NIPN 2020).

Addressing these challenges requires improving dietary diversity and involves expanding food sources to ensure adequate nutrient supply. This strategy encompasses leveraging energy and protein from various ecosystems, including croplands, grasslands, forests, and oceans, and exploring plant, animal, and microbial food sources (Qaim 2024). Such approaches are vital in Asia, where unique geographical advantages provide opportunities for dietary expansion. Asia’s diverse landscapes, from coastal regions to fertile plains, offer immense potential for improving dietary diversity. Countries like Viet Nam, Indonesia, and Thailand benefit from abundant seafood resources, integrating them into iconic dishes such as Vietnamese shrimp spring rolls and Thai curry crab. Expanding the use of algae, seaweed, and fermented foods, already part of traditional Asian diets, can further enhance nutrition and sustainability.

Policy Implications

Several policy directions can be pursued to achieve the goal of improving dietary diversity.

First, promoting diversified agricultural production is a key channel for improving dietary diversity. Mehraban and Ickowitz (2021) reported that the decline in household production diversity in Indonesia led to a corresponding reduction in dietary diversity, primarily driven by decreased consumption of nutritious food groups such as fruits, vegetables, legumes, and fish. Thus, encouraging smallholder farmers to diversify agricultural production by producing staples like rice, vegetables, and fruits simultaneously can significantly enrich food sources without compromising their livelihoods. These efforts can be supported through targeted programs and subsidies to incentivize the cultivation of diverse crops.

Second, increasing the commercialization of agriculture accelerates the market circulation of diverse agricultural products. This not only enhances the availability of diverse foods but also allows farmers to earn higher incomes, enabling them to purchase various nutritious foods (Zheng and Ma 2023). Policymakers should focus on developing robust agricultural markets and supply chains to facilitate this transition.

Third, online markets offer a more extensive and varied selection of foods than traditional local markets, making it easier for residents to access diverse food options even when self-production is not feasible (Ma et al. 2022). Investments in infrastructure, such as logistics and delivery systems, are crucial for expanding access to online shopping platforms and ensuring their widespread adoption. In addition, training for individuals with lower levels of education can help them to effectively navigate and shop for food online. This training should focus on building digital literacy, understanding online platforms, comparing prices, and identifying nutritious and cost-effective options to ensure they can make informed purchasing decisions in the digital marketplace.

Fourth, changing dietary habits requires improving awareness of the benefits of dietary diversity. Nutrition training programs can help residents overcome reliance on traditional nutritional practices and understand the importance of incorporating diverse foods into their diets (Zheng et al. 2023). Such programs can be implemented through local governance structures, community organizations, and NGOs to ensure broad reach and impact.

Hongyun Zheng extends his gratitude to the National Natural Science Foundation of China (72303076).

References

Ahmed, A., F. Coleman, J. Ghostlaw, J. Hoddinott, P. Menon, A. Parvin, A. Pereira, A. Quisumbing, S. Roy, and M. Younus. 2024. Increasing Production Diversity and Diet Quality: Evidence from Bangladesh. American Journal of Agricultural Economics 106(3): 1089–1110.

Baden, M. Y., G. Liu, A. Satija, Y. Li, Q. Sun, T. T. Fung, E. B. Rimm, W. C. Willett, F. B. Hu, and S. N. Bhupathiraju. 2019. Changes in Plant-Based Diet Quality and Total and Cause-Specific Mortality. Circulation 140(12): 979–991.

Carrasco, B., Q. Zhang. 2022. Confronting Asia’s Triple Threat: Climate Change, Biodiversity Loss, Food Insecurity. Asian Development Blog. 27 September.

FAO. 2024. The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2024.

Geyik, Ö., M. Hadjikakou, and B. A. Bryan. 2023. Climate-Friendly and Nutrition-Sensitive Interventions Can Close the Global Dietary Nutrient Gap While Reducing GHG Emissions. Nature Food 4(1): 61–73.

Lucas, E., M. Guo, and G. Guillén-Gosálbez. 2023. Low-Carbon Diets Can Reduce Global Ecological and Health Costs. Nature Food 4(5): 394–406.

Ma, W., P. Vatsa, H. Zheng, Y. Guo. 2022. Does Online Food Shopping Boost Dietary Diversity? Application of an Endogenous Switching Model with a Count Outcome Variable. Agricultural and Food Economics 10(1): 30.

Mehraban, N., and A. Ickowitz. 2021. Dietary Diversity of Rural Indonesian Households Declines Over Time with Agricultural Production Diversity Even as Incomes Rise. Global Food Security 28: 100502.

Miyamoto, K., F. Kawase, T. Imai, A. Sezaki, and H. Shimokata. 2019. Dietary Diversity and Healthy Life Expectancy—An International Comparative Study. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition 73(3): 395–400.

Nie, J., C. Yu, Y. Guo, P. Pei, L. Chen, Y. Pang, H. Du, L. Yang, Y. Chen, S. Yan, J. Chen, Z. Chen, J. Lv, and L. Li. 2021. Tea Consumption and Long-Term Risk of Type 2 Diabetes and Diabetic Complications: A Cohort Study of 0.5 Million Chinese Adults. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 114(1): 194–202.

NIPN. 2020. National Nutrition Profile.

Qaim, M. 2024. Sustainability of Animal-Sourced Foods and Plant-Based Alternatives. Nature Food 121(50): 1–8.

Wang, X, B. L. Bodirsky, C. Müller, K. Z. Chen, and C. Yuan. 2022. The Triple Benefits of Slimming and Greening the Chinese Food System. Nature Food 3(9): 686–693.

Yu, G., R. Lu, J. Yang, M. L. Rahman, L. J. Li, D. D. Wang, Q. Sun, W. W. Pang, C. Guivarch, A. Birukov, J. Grewal, Z. Chen, and C. Zhang. 2024. Healthy Dietary Patterns Are Associated with Exposure to Environmental Chemicals in a Pregnancy Cohort. Nature Food 5(July).

Zheng, H., and W. Ma. 2023. Impact of Agricultural Commercialization on Dietary Diversity and Vulnerability to Poverty: Insights from Chinese Rural Households. Economic Analysis and Policy 80: 558–569.

Zheng, H., W. Ma, and Y. Guo. 2023. Does Nutrition Knowledge Training Improve Dietary Diversity and Nutrition Intake? Insights from Rural China. Agribusiness 39(S1): 1417–1436.

No comments yet.