Many developing countries struggle with the dichotomy of acquiring land for infrastructure development and balancing landholder interests. Industrialization of rural villages across developing Asia (particularly in India) has created widespread social and political tensions in the recent past. Most of these are attributed to land acquisition (Sarkar 2007). The “right” of sovereignty on land has long been a contested subject. Even in democracies, the exigencies of collective benefit versus individual land rights have been at loggerheads. In the long run, growth dividends from infrastructure development and industrialization are likely to materialize (Paul and Sarma 2017), and acquisition of land to facilitate this process remains one of the main development challenges in many Asian countries.

Policy and academic debate have since heavily focused on the issue of compensation—seen as the tool for achieving so-called Pareto improvements where development-led land acquisition does not make anyone worse off (Kanbur 2003). Households are reluctant to sell their inherited land for infrastructure and industrialization purposes, since an optimum compensation does not guarantee a windfall in the long term. As a result, the risks associated with investment in infrastructure and industrialization—and subsequent change in land ownership—are very high. The underlying assumption regarding compensation is that the acceptance or tolerance of land grab and ensuing displacement is a function of the monetary compensation laid out in the precedence of such acts. The recent political upheaval transgressing from the industrialization drive through forcible land grab in many parts of Asia (India, Indonesia, Nepal, and the Philippines in particular) exacerbates this problem further. All these factors point to the need for a sustainable policy—a framework that results in a positive sum game that benefits the landowners without hurting the growth prospects. In a recent study, we focus on such a framework using land trust policies.

Present value model

We consider a present value model, as it provides a way to relate the current price of land to the infinite streams of future earnings from holding the land. In classical rent theory, Ricardo (1817) mentions that land rent is the payment that the landowner receives “for the use [by himself or someone else] of the original and indestructible powers of the soil.” Although this was put in the context of agricultural use, we extend this notion to the use of land for nonagricultural purposes (infrastructure, industrialization, etc.).

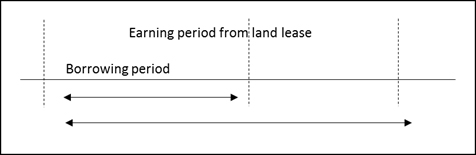

For projects that are related to infrastructure (e.g., building roads or railways), it is often the case that the landowners lease their land out to the government or private organizations (who are responsible for the construction work with land trusts as intermediaries) and then relocate. The landowners borrow to cover their relocation expenses with an annuity plan that runs for n periods, which is shorter than the time they enjoy rental incomes (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Earning versus borrowing period

Based on our model, it becomes an acceptable (or binding) condition for rational landowners to invest their land for an infrastructure project if their net income from the land exceeds their previous earnings from the land (this approach assumes that the landowners derive utility from the land purely in economic terms). Land trusts or land leases play an integral role in providing assurance on the quantum and regularity of land rent. Since the borrowing cost for relocation is fixed and set by the commercial lender (assumed to be a commercial bank), the landowners face risks arising from fluctuations in or nonpayment of land rents. Use of land trusts or land leases may help reduce the risks associated with land rents. Land trusts may also help reduce the disutility landowners experience from losing their land (emotional, cultural ties) by engaging the landowners as trustees who are integral parts of the development of communities. Once we introduce spillover tax revenue into the model, the rental income goes up. This makes the landowners more willing to accept offers from the land trust organizations.

Land trust structure

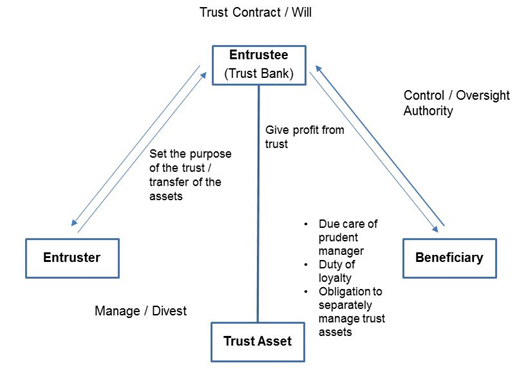

There are three bodies of trust: entruster, entrustee, and beneficiary (Figure 2).

Figure 2. The three bodies of trust

When entrusters have an asset that they wish to leave for a beneficiary, but do not want to give it away immediately, they may “entrust” the entrustee with the asset with certain conditions for the beneficiary to receive the profit. This method can be used for trust by will. The entrustee must manage the trust asset by adhering to the following three rules:

- Due care of prudent manager: Entrustee must manage the trust asset with due care of a prudent manager.

- Duty of loyalty: Entrustee must manage the trust asset for the beneficiary following the purpose of the trust. Entrustee must not use the trust asset for his or her own benefit or a third party.

- Obligation to separately manage trust assets: Entrustee must manage the trust asset apart from the beneficiary’s property or any other properties.

Efficiency gains from land trust policies

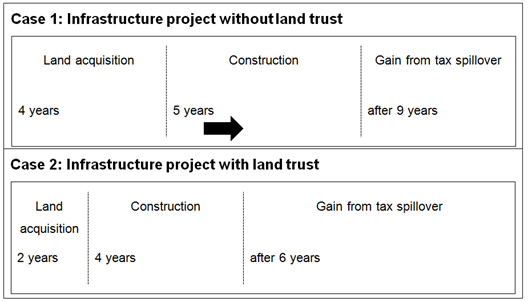

Figure 3 illustrates two scenarios. The top panel shows an infrastructure project that takes about 4 years to acquire land through various negotiations followed by a construction period of 5 years, after which landowners start enjoying the spillover benefit from an increase in tax collection. It is feasible to expedite this process by using a land trust bank, as shown in the bottom panel. In the case of the land trust bank, land acquisition is handled in a much more peaceful and coordinated manner, where the landowners are relocated to a new place with some positive net earnings from the land. As a result, the benefits from a tax spillover can take place without waiting 9 years; the construction time is also reduced because there is less uncertainty about the land acquisition.

Figure 3. Gains from land trust bank

Many parts of Asia—not limited to India, Indonesia, Nepal, and the Philippines—have witnessed a surge in political challenges and change that go beyond the industrialization drive through forcible land acquisition. This highlights an urgent need for a sustainable policy framework that is holistically relevant, benefiting the landowners without hurting the growth prospects. Our model, based on net present value, proposes land trusts or land leases for the development of infrastructure investment and industrialization purposes without infringing on the rights of the landowners.

_____

References:

Kanbur, R. 2003. Development Economics and the Compensation Principle. International Social Science Journal 55(175): 1–18.

Paul, S., and V. Sarma. 2017. Industrialisation-Led Displacement and Long-Term Welfare: Evidence from West Bengal. Oxford Development Studies 45(3): 240–59.

Ricardo, D. 1817. On the Principles of Political Economy, and Taxation. London: John Murray.

Sarkar, A. 2007. Development and Displacement: Land Acquisition in West Bengal. Economic and Political Weekly 42(16): 1435–42.