Small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) are a very important part of Asia’s economy. In this article, we explore SMEs and their financing issues with respect to the performance of SMEs in international trade, based on the sample of more than 8,000 companies across the People’s Republic of China (PRC) and Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) member states. The discussion is derived from a recent Asian Development Bank Institute (ADBI) working paper (Jinjarak, Mutuc, and Wignaraja 2014).

The great collapse both of the world economy and that of Asia in the post–global financial crisis era as well as the subsequent trade collapse highlighted the finance–trade link. The downturn in trade finance was a major issue during that crisis. Since 2008, we have had a recovery in trade and in growth to some extent, partly due to a lot of fiscal and monetary stimulus, and Asia is exporting its way to growth. However, we are not quite certain of what is happening to firms in this whole story. This issue is worth studying because it is so important for inclusive growth in Asia.

Importance of SMEs on output, employment, and trade in developing East Asia

When people think of inclusive growth, they normally think of education and health as important parts of the growth story. SMEs, however, are also vital as a vehicle to create jobs and therefore ensure more participation of the poor in economic development in Asia. The literature emphasizes that firms differ in their characteristics. Some firms are better than others in terms of being able to participate in trade as well as business activity. We want to analyze the characteristics of firms that do better than others in terms of trading, whether size is a factor in this game, and what role finance plays.

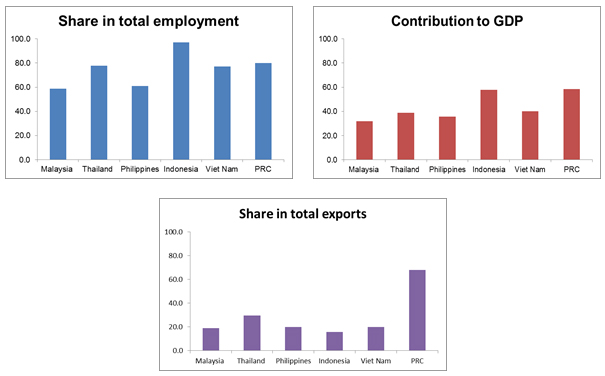

Figure 1 gives a macro view of SMEs in the PRC and the ASEAN economies in terms of their share of employment, contribution to gross domestic product (GDP), and exports. The data suggest that SMEs are not only very important in economic activity in Asia, particularly in employment, but also somewhat important in GDP. Of course, the economies differ, however, because of the ways in which SMEs are represented in the industrial structure. Also, in part, the definitions of what constitutes an SME vary between these economies. While SMEs are important in economic activity, they are less important in trade in ASEAN economies. Interestingly, the PRC has relatively high SME export shares.

Figure 1: Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises in Employment, GDP, and Total Exports (%)

GDP = gross domestic product, PRC = People’s Republic of China, SMEs = small and medium-sized enterprises.

Data are drawn from various statistical agencies (Association of Southeast Asian Nations SME data, Business in Asia, Department of Trade and Industry Philippines, PRC Ministry of Industry and Information Technology).

Source: Authors’ calculations on World Bank Enterprise Survey data.

How SMEs performance in trade, financing issues, and other factors are linked

There are many channels through which finance plays a role in terms of business activity—and trade also comes into play. For instance, during the global financial crisis, the tightening of credit conditions may have discouraged many possible trade transactions. We think it is not just a one-way relationship; there are actually two-way feedbacks. Trading thus helps access to finance and that is part of our story from the macro point of view. Exports determine which industries in a country need more working capital.

It is worthwhile to examine different relationships between finance, trade, and SMEs. These include what are the characteristics of firms that trade, how does finance play a role in this, and what are the other characteristics of firms that come into play? Is it just size or are there other factors that matter? We use the data from the World Bank Enterprise Survey, which includes a large number of economies, and we selected the PRC and some ASEAN economies. The total Asian sample covers a multitude of sectors in about 8,000 randomly selected firms.

More pertinent for our new study is the microeconomic literature that we will be putting to the test. Melitz (2003) points out that some firms trade better than others and the characteristics of firms are related to trade costs. He argues that only the really productive firms were able to export. That notion has been tested by others, which further extends this idea to productivity also being linked to finance and access to finance being important.

There is related literature coming from Neo-Heckscher–Ohlin models as well as theories of technology and trade that suggest that there are other factors, apart from productivity and finance, which are also important when it comes to looking at trade. Foreign ownership, for instance, is important, as are skills and technology, among others. The differentiated firm that gets into exports is not only productive but needs finance, and has all these other characteristics associated with it. So scale and firm size matter.

Further, on the relationship between firm size and exports, standard treatment in theory assumes that large firms are more competitive in exports compared to SMEs because large firms have more resources to meet the fixed costs of exporting. The literature assumes that SMEs are at a disadvantage because they lack the resources and networks needed to trade, and they suffer disproportionately from market imperfections and regulations. SMEs are also likely to be disproportionately affected by financial crises and economic downturns, including being deprived of access to credit.

Hence, there are many factors that affect firms’ business performance. Our focus is on one of the most important factors—finance. The International Finance Corporation (IFC) estimates the value of the credit gap, which is the difference between the formal credit provided to SMEs and SMEs’ total estimated potential need for formal credit. The IFC data indicate that 8 million SMEs in Asia and the Pacific do not have sufficient access to finance. The credit gap per SME is larger in more developed in ASEAN economies, such as Malaysia and Thailand, than in others. This partly reflects credit needs at different levels of development.

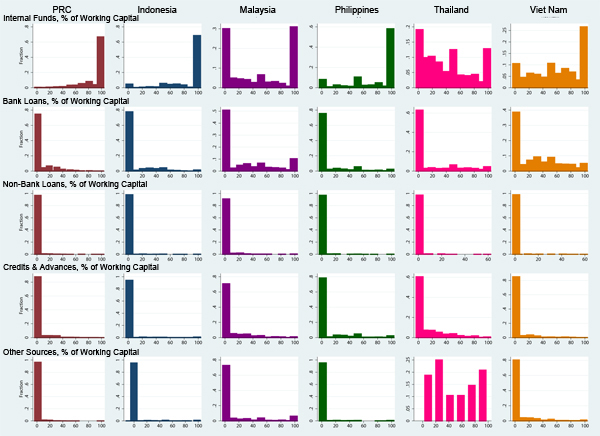

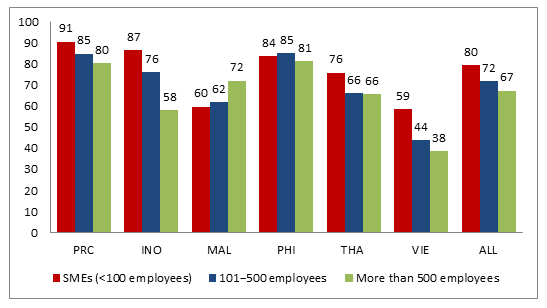

Turning to the firm-level sample, Figure 2 reports the composition of financing sources for the SMEs in our sample and Figure 3 provides by firm size category the percentage of firms that rely on bank loans for less than 25% of their working capital. Strikingly, about 76% of all SMEs in our Asian sample of 8,000 firms rely on bank loans for less than 25% of their working capital. The number falls as the firms get larger. It is a general problem of access to bank credit, but it is highest for the SME section and varies by country. Of course, in Malaysia and Thailand, the numbers are a bit different, and that may also be because they are more developed than others and perhaps have more open capital markets and better industrial structures than the other economies.

Figure 2: Patterns of SMEs’ financing sources

Source: Author’s calculations on World Bank Enterprise Survey data.

Figure 3: Importance of bank loans by firm size (% of firms, bank loans < 25% of capital)

Note: PRC – People’s Republic of China; INO – Indonesia; MAL – Malaysia; PHI – Philippines; THA – Thailand; VIE – Viet Nam.

Source: Author’s calculations on World Bank Enterprise Survey data.

Looking at the econometric exercise, we modeled what drives trade, looking at the issue of finance as well as firm size, and then we examined the interrelationships between these variables. We find that being an SME is negatively correlated with trading performance measured by exports-to-sales ratios. Thus, SMEs suffer or conduct less trade compared to large firms. Bank borrowing and trade credit are positively correlated with export participation.

Policy implications and further considerations

Essentially, we find it very useful to combine macro data with micro data when it comes to studying this issue of firm size, trade, and finance, particularly after the global financial crisis of 2008–2009. We believe that the worldwide trade recovery is linked to the importance of understanding the resilience and different strengths in Asia’s industrial structure. When we break the data down by economy into the PRC and ASEAN economies, which are very important in the trade recovery because they are the bulk traders in Asia, we find that financial development and availability of credit matter for trade.

SMEs are very important in economic activity but not so much in international trade, and a lack of credit is a major constraint for SMEs, particularly when it comes to export performance. The firm-level results confirm this interesting finding. In the econometric analysis, we also find that a two-way relationship with exporting is positively related to finance. Thus, the medium-sized firms are an interesting area for future study, because being very small is a big disadvantage in trading and also in attracting access to finance. Being medium sized may be better in this vein.

Our analysis opens up four fascinating policy questions. The first question is about the missing middle. There are a lot of discussions about the medium end of firms—depending on which definition is used, this could mean firms between 100 and up to 200 employees, or between 50 and 100 employees. Are medium-sized firms a driver both of exporting and accessing finance? We shall explore this further in our research.

The second question is: what role should central banks and financial supervision agencies play in looking at credit allocation, particularly for financial inclusion, and how far should this go? Should it really move toward directed credit or should we be talking about the most market-based system with some elements of self-selection? The third important question relates to credit targeting. Should we consider targeting geographies where we know there are vulnerable entrepreneurs and firms? Should we be looking at gender issues of financial inclusion in this aspect?

The last question we think is important from this whole discussion is: what complementary policies of nonfinancial support should we be considering? Finance is important, but there are many other factors (such as technical efficiency, research and development, skills creation, distribution and marketing efforts, and attracting foreign investment) that influence the trading activity of firms. SMEs also have to face non-tariff barriers, i.e., environmental and labor regulations, product standardization, and language, law, and documentation issues. As the success of German Mittelstand suggests, developing East Asia needs to improve the economic, political, and institutional environment to be more supportive to SMEs, as well as improve entrepreneurship with social responsibility (Paust 2014). It would also be essential to consider the issues of SMEs, their finance and business support in the context of how they are linked with large corporations and entry into global value chains as an active agenda.

_____

References:

Jinjarak, Y., P. J. Mutuc, and G. Wignaraja. 2014. Does Finance Really Matter for the Participation of SMEs in International Trade? Evidence from 8,080 East Asian Firms. ADBI Working Paper Series No. 470. Tokyo: Asian Development Bank Institute.

Melitz, M. J. 2003. The Impact of Trade on Intra-Industry Reallocations and Aggregate Industry Productivity. Econometrica 71(6): 1695–1725.

Paust, S. 2014. The German Mittelstand – a model for Asia’s emerging economies? Asia Pathways. ADBI.