The decades leading to the current global economic turmoil saw many developing countries attempt to pursue the East Asian development model, which is widely perceived to have been export-led. Is such growth possible in the post-crisis world with shrinking global imbalances? Historical data may provide useful clues. Our paper, titled “Can Asia Sustain an Export-Led Growth Strategy in the Aftermath of the Global Crisis? An Empirical Exploration“, finds that Asian growth in the pre-crisis period was significantly correlated with the proportion of their manufactured exports that were sold in industrialized country markets. Given this evidence, Asian exports to other developing countries may not be good substitutes for their exports to developed countries. The policy implication is clear: a deceleration of exports to industrialized countries may limit prospects for post-crisis growth even if exports to other developing countries pick up the slack. Asian policy makers should, therefore, be more willing than ever to experiment with new paths to technological catch up.

The decades leading to the current global economic turmoil saw many developing countries attempt to pursue the East Asian development model, which is widely perceived to have been export-led. Is such growth possible in the post-crisis world with shrinking global imbalances? Historical data may provide useful clues. Our paper, titled “Can Asia Sustain an Export-Led Growth Strategy in the Aftermath of the Global Crisis? An Empirical Exploration“, finds that Asian growth in the pre-crisis period was significantly correlated with the proportion of their manufactured exports that were sold in industrialized country markets. Given this evidence, Asian exports to other developing countries may not be good substitutes for their exports to developed countries. The policy implication is clear: a deceleration of exports to industrialized countries may limit prospects for post-crisis growth even if exports to other developing countries pick up the slack. Asian policy makers should, therefore, be more willing than ever to experiment with new paths to technological catch up.

A little bit of background may help put our study in perspective. Some scholars have recently argued that developing countries have “decoupled’’ from Europe and the United States, and that the slowdown in the developed countries should, therefore, not significantly affect the development prospects of the South. Canuto, Haddad, and Hanson (2010), for example, suggest that we may be witnessing the emergence of “Export-Led Growth V2.0,’’ where South-South exports substitute for South-North exports. This interpretation implies that exports contribute to growth regardless of their destination.

Rodrik (2009), on a related note, has argued that Asian growth successes were based on broader tradable sector growth rather than solely on exports. Thus, there is something special about the tradable sector. The tradable sector in Asian countries is typically associated with industrial production. If Rodrik’s argument is empirically valid, then shrinkage of global imbalances should not be an obstacle to post-crisis Asian growth since domestic demand for tradables can substitute for exports.

A relatively recent strand of trade literature, inspired by Melitz (2003), however, indicates hitherto underexplored gains from exporting. Empirical studies find that exporting firms tend, on average, to be more productive. This suggests either that more productive firms self-select into export markets, and/or that exporting firms become more productive over time. The latter may happen due to several reasons such as economies of scale, dynamic learning, technological spillovers, and competitive pressures. Pack (2001), for example, notes that international competition allowed purchasers abroad to exert heavy pressure on East Asian exporters — producing under contract — to cut costs and increase efficiency. Exporting firms may have easier access to new technologies thanks to their international links. Moreover, exporting firms may receive technical guidance on how to meet higher quality standards from their clients. Again, Pack notes that export-oriented production encouraged East Asian countries to move toward more sophisticated technology to meet the complex contractual requirements from Western countries. This is not surprising for developing countries since they tend to be farther from the technological frontier, and hence have greater scope for learning. Thus, to the extent that the externalities due to exports are associated more strongly with sales to developed countries, we would expect the proportion of a country’s exports destined for these countries to be a significant contributor to productivity and output growth.

In our paper, we explore prospects for continued export-led growth by first contrasting the several interpretations associated with this term. We then investigate post-crisis prospects by trying to empirically identify the interpretation most relevant to pre-crisis growth. In particular, we focus on an aspect neglected in the expanding literature on global imbalances: the destination structure of a country’s exports. Our sample consists of a maximum of 44 Asian developing countries, 20 industrialized countries, and the time period 1953–2009. To remove short-run cyclical effects, we use data averaged over 3-year intervals. Employing panel data techniques to distinguish between different kinds of export- and tradable-led growth we find that, among our variables of interest, the proportion of a country’s manufactured exports that is destined for industrialized countries is the one most robustly associated with output growth. The industrial share of GDP, used as a proxy for the size of the tradable sector, too is positively associated with growth, but the long-run effect is statistically insignificant in most cases. We obtain similar results from dynamic panel estimates after controlling for potential endogeneity and simultaneity issues. In addition, we find that our results are robust to changes in sample composition and time periods, and to the exclusion of outliers. A crucial implication is that prospects for a new sustained episode of growth, this time centered on domestic tradable consumption or on other developing countries as export markets, may be limited.

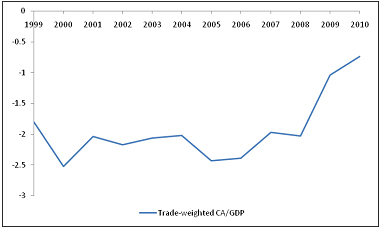

Global re-balancing will require a decline in industrial country trade deficits. Figure 1, which presents the trade-weighted average current account of the industrialized countries in our sample, suggests that global imbalances have already begun to shrink. In principle deficits could decline through greater industrialized country export growth without a concurrent fall in import growth. However, the near certainty of slower industrialized country income and demand growth leads one to conclude that Asian exports to these countries are likely to be negatively impacted. This, in light of our main finding, is a cause for concern. Put differently, the fact that tradable production for domestic consumption or export to developing countries may not be good substitutes for exports to industrialized countries magnifies the challenges facing sustained Asian growth in the coming years. Export-led growth v2.0 in this sense may not be a good substitute for export-led growth v1.0. Asian policy makers, anticipating shrinking or stagnant industrialized country markets may do well to balance their pursuit of greater intra-Asian trade with other, perhaps yet unexplored, avenues for technological catch-up.

Figure 1: Trade-Weighted Current Account as a Proportion of Gross Domestic Product for the 19 Industrialized Countries in Our Sample, 1999–2010

Source: United Nations COMTRADE (2011) and authors’ calculations

_____

References:

Melitz, M. 2003. The impact of trade on intra-industry reallocations and aggregate industry productivity. Econometrica 71(6):1,695–1,725. November.

Pack, H. 2001. Technological change and growth in East Asia: Macro versus microperspectives. In Rethinking the East Asian Miracle edited by J. Stiglitz and S. Yusuf. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Park, A., D. Yang, X. Shi, and Y. Jiang. 2009. Exporting and firm performance: Chinese exporters and the Asian financial crisis. Working Paper 14632. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research. January.

Razmi, A. and Hernandez, G. 2011. Can Asia sustain an export-led growth strategy in the aftermath of the global crisis? An empirical exploration. Working Paper 329. Tokyo: Asian Development Bank Institute. December.

Rodrik, D. 2009. Growth after the crisis. Working Paper 65. Washington, DC: Commission on Growth and Development.