The World Health Organization (WHO) defines malnutrition as imbalances in the dietary intakes of individuals that can cause deficiencies and excesses. It covers two broad issues—undernutrition and overnutrition (overweight, obesity, and diet-related noncommunicable disorders). The severity of child undernutrition is determined by the growth-faltering parameters of stunting, wasting, underweight, and micronutrient deficiencies, while overweight/obesity is defined as having a high body mass index and is linked to metabolic disorders, including diabetes, stroke, and cancer.

The “triple burden” of malnutrition comprises three types of nutritional problem: undernutrition, overnutrition or obesity, and micronutrient deficiency in individuals, households, and populations. Due to inadequate amounts or poor quality of complementary feeding and family foods, children from disadvantaged groups are particularly prone to developing nutrient deficiencies and growth problems. High infection rates and contagious diseases further exacerbate the issue, especially in developing regions.

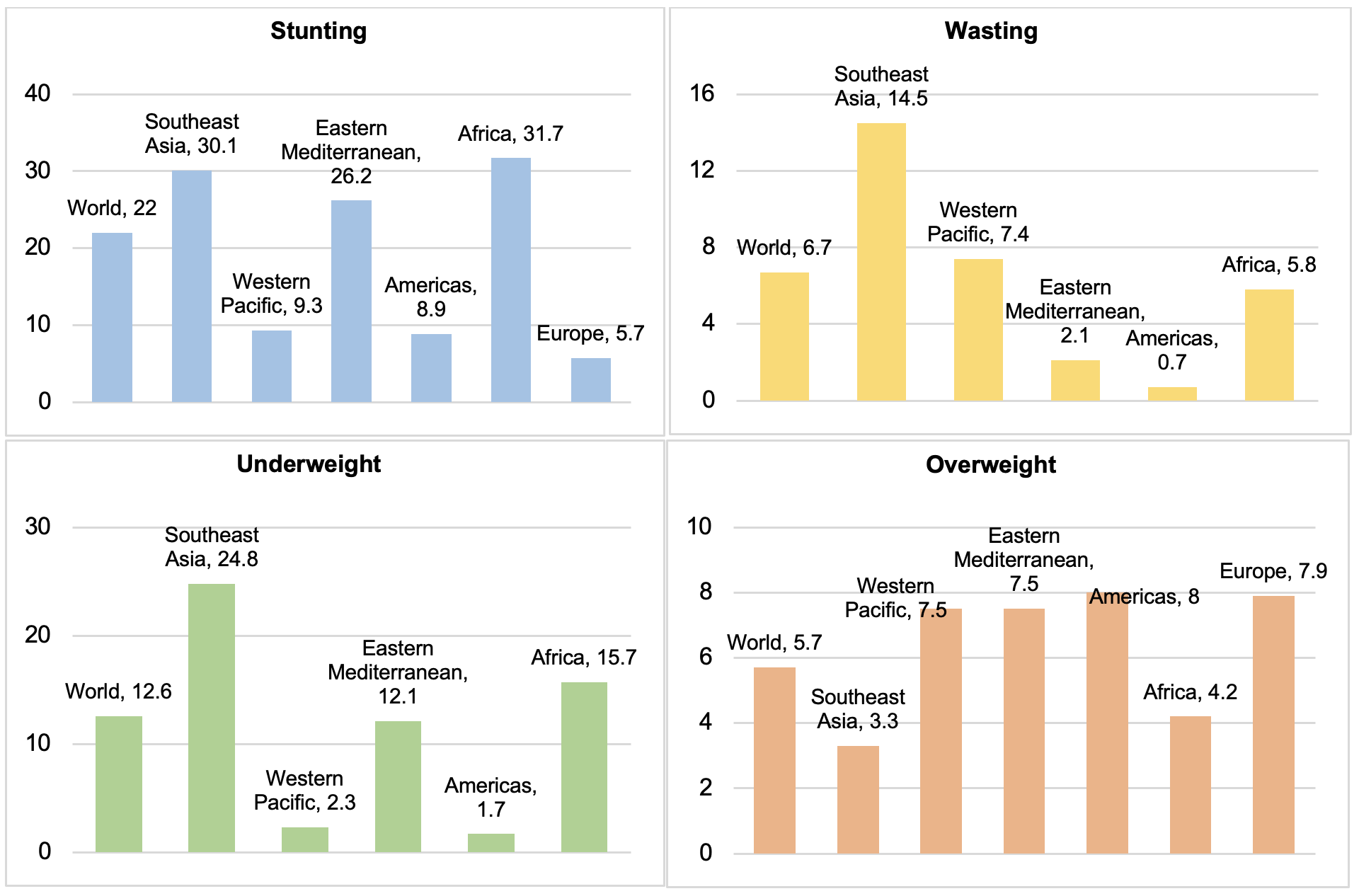

Despite significant progress and investment by national governments and international agencies to alleviate undernutrition, a large number of children under 5 suffer from undernutrition (Figure 1). The problem of undernourishment is also concentrated particularly in Southeast Asia and Africa.

Figure 1: Prevalence of Malnourishment in Children under 5 by Region (%)

Data source: World Health Organization. Global Health Observatory.

https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/indicators/indicator-details [1] (accessed 29 November 2022).

Undernourishment: A long-standing problem facing children in the developing world

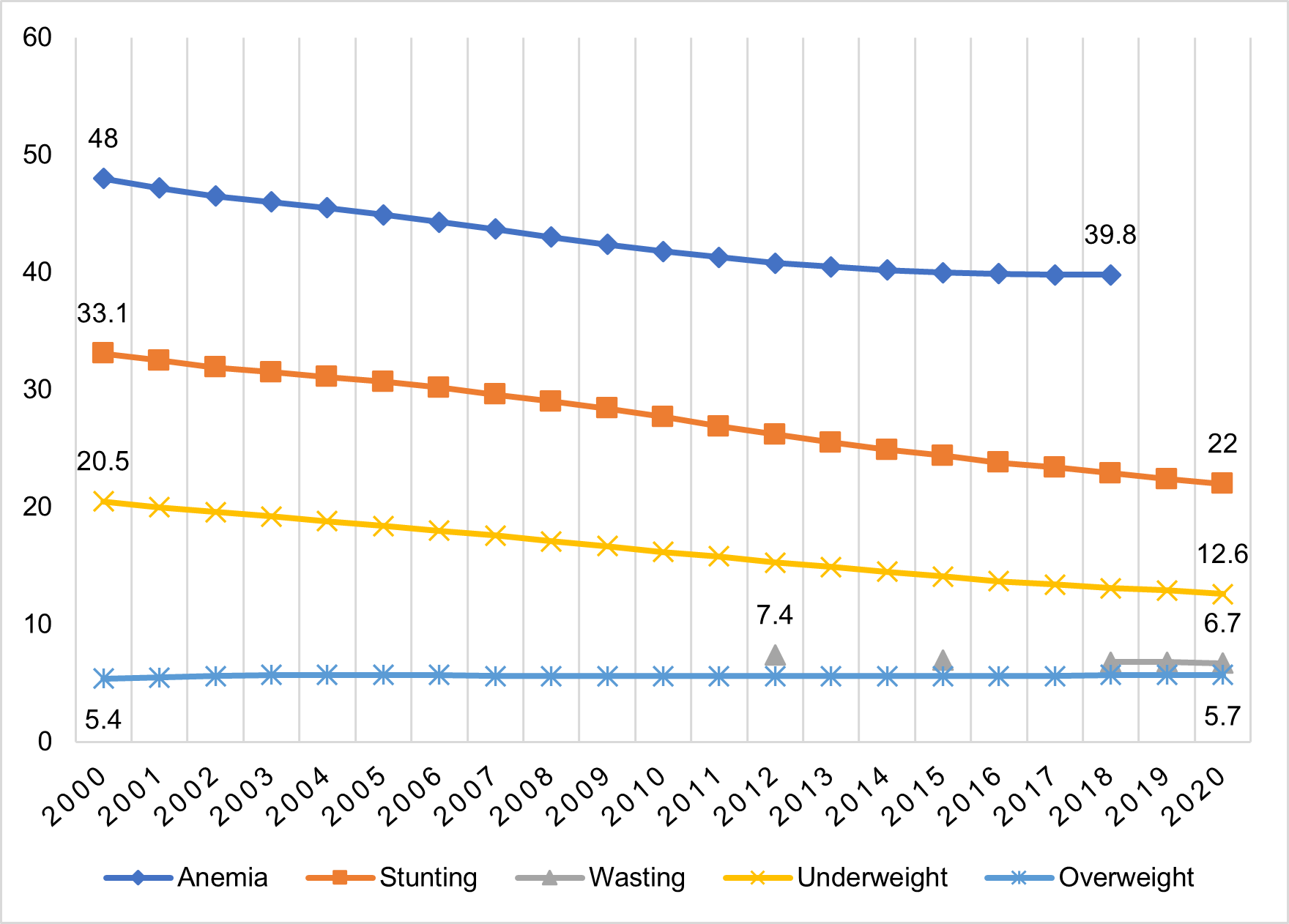

Underweight refers to low weight to age and captures short-term loss. Magnitudes remain high despite improvements in most indicators over the past few decades (Figure 2). In 2020, the WHO reported 149 million stunted children under 5 and 45 million suffering from wasting worldwide.

Figure 2: Global Trend of the Triple Burden of Nutrition in Children under 5 (%)

Note: Undernourishment in children is measured as inadequate growth during the first 5 years of life. Stunting is an indicator of long-term deprivation and refers to the poor linear development of a child for their age. Wasting is measured as low weight for height and represents acute undernourishment due to illnesses or a scant diet.

Note: Undernourishment in children is measured as inadequate growth during the first 5 years of life. Stunting is an indicator of long-term deprivation and refers to the poor linear development of a child for their age. Wasting is measured as low weight for height and represents acute undernourishment due to illnesses or a scant diet.

Data source: World Health Organization. Global Health Observatory. https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/indicators/indicator-details [1] (accessed 29 November 2022).

Undernutrition not only impairs children’s initial growth years but also impacts their health and economic prospects for the remainder of their lives (Nugent et al. 2020). Evidence suggests that it makes them highly susceptible to obesity and metabolic disorders in adulthood and causes the inter-generational transmission of malnutrition (Sawaya et al. 2003).

Overweight and obesity: No longer only a problem for the developed world

Previously thought as a problem only in high-income countries, being overweight has become a common problem in low- and middle-income countries at the same time as undernutrition (see Figure 1). In 2020, the WHO estimated that around 39 million children under 5 years were overweight or obese, and almost half of them live in Asia.

Several studies have suggested that overnutrition is associated with urbanization and higher income levels—however, it is no longer confined to urban areas. Recent studies have shown no significant difference between overweight and obesity among adults in rural and urban areas in developed and developing regions (Trivedi et al. 2015; Kumari et al. 2022).

Hidden hunger and micronutrient deficiency: A critical emerging public health issue

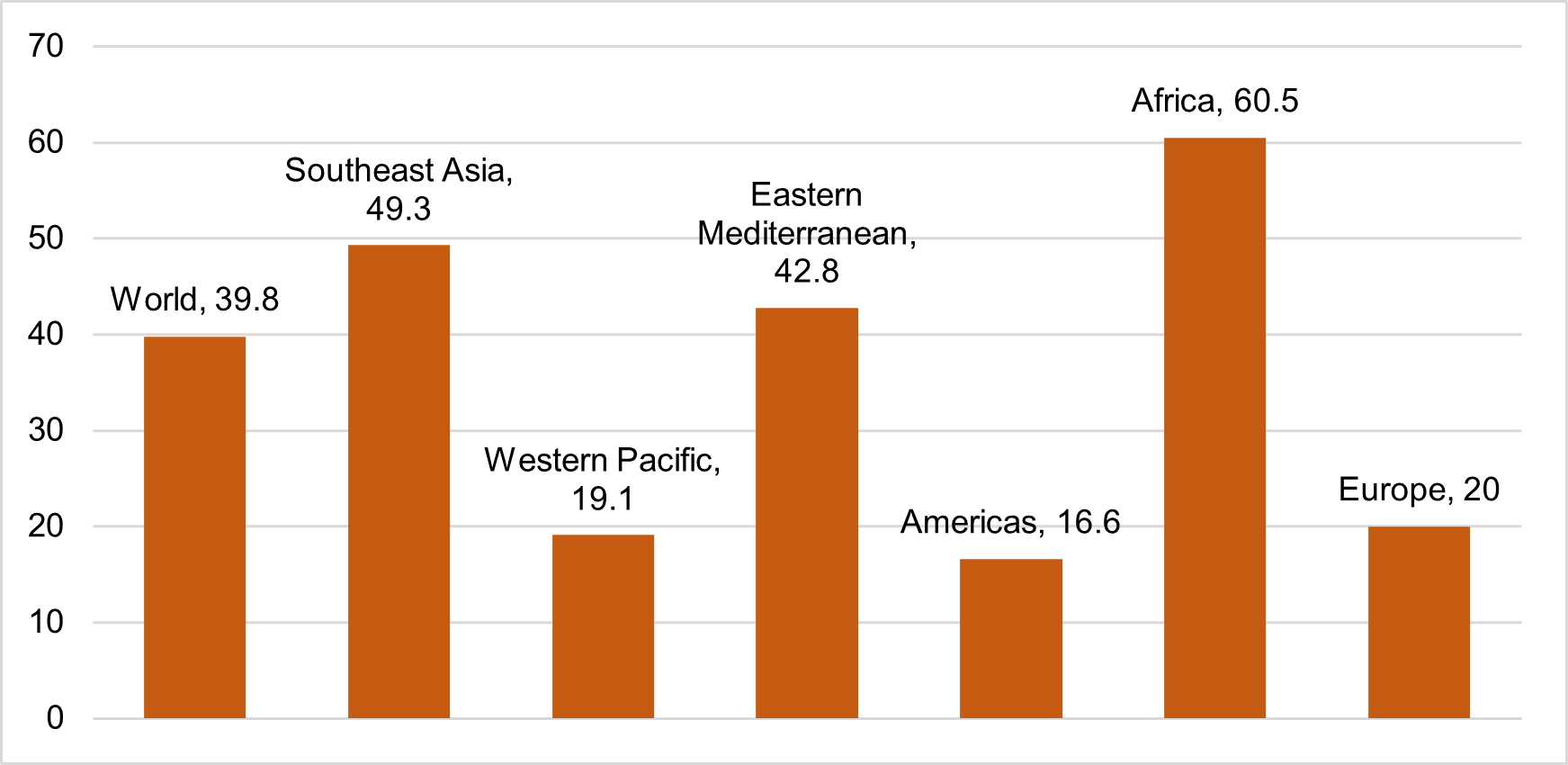

A deficiency of essential micronutrients like vitamin A, zinc, iron, folate, and vitamin B12 is widespread in developing regions with an increasing prevalence in developed areas. Anemia is one of the critically severe manifestations of hidden hunger among children, adolescents, and adults. In 2019, the WHO reported that approximately 40% of children under 5 suffer from anemia globally (see Figure 3). Prevalence is lowest in the higher-income regions of North America, Europe and Central Asia, and East Asia and the Pacific. However, South Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa are severely affected, with 55% and 60% of children being anemic (World Health Organization (via World Bank), n.d.). Zinc and vitamin A deficiency are other more prevalent micronutrient deficiencies among children.

Figure 3: Percentage of Children under Five with Anemia by Region (%)

Data source: World Health Organization. Global Health Observatory.

Data source: World Health Organization. Global Health Observatory.

https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/indicators/indicator-details [1] (accessed 29 November 2022).

The triple burden of malnutrition: Global food transition and paradigm shift

Once considered a clinical problem localized to poor regions of the world, malnutrition is finally being realized as a social, political, and economic issue. The measurement criteria and definitions of estimating malnutrition may vary. Still, their coexistence in geographical regions, households, and individuals worldwide has pointed out systemic changes in food systems, dietary patterns, and increasing inequality in terms of the availability, accessibility, and affordability of nutritious food.

Food systems are intrinsically complex and unique to geographical and cultural settings. However, the global food system transition has made unhealthy food cheaper and easily accessible (Popkin et al. 2020). Through fiscal subsidies, several countries have expanded access to staples such as wheat, rice, corn, and their derivatives. As a result, unsubsidized or less-subsidized commodities like fruits, vegetables, and pulses have become relatively more expensive and discouraged from being consumed. (Chakrabarti et al. 2018; Gillespie et al. 2021).

Several other factors have contributed to the prevalence of malnutrition in developing areas. This includes improvements in life expectancy due to a shift in disease burden from infectious to noncommunicable diseases and rapid economic development leading to higher availability and affordability, particularly high-carbohydrate and processed products. Unplanned, highly dense urban areas have further added to the burden by discouraging physical activity.

The challenge ahead: Policy implementation and future pathways

Climate change, conflicts, and the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic have caused disruptions and the collapse of international food supply chains in many regions of the world. According to the Food and Agriculture Organization, in 2020, almost 3.1 billion people could not afford a nutritious diet, an increase of 112 million since 2019, reflecting the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on consumer food prices (FAO et al. 2022).

While approaching the problem of malnutrition in all its forms, policy makers must understand the regional nuances and challenges. It is imperative that they acknowledge that malnutrition is not just a clinical issue but more of a socioeconomic, cultural, and political challenge. Hence, a one-size-fits-all approach may never work, especially in countries with high populations and cultural diversity.

Several studies have continuously pointed out that food quality, more than quantity, correlates with malnutrition (Pinstrup-Andersen 2007; White et al. 2017). Most nutrition policies, especially in developing regions, still focus on providing enough calories rather than meeting children’s nutritional requirements (Afridi 2010). Both food insecurity and energy-dense, high-sugar foods result in micronutrient deficiencies. In the presence of undernutrition or obesity, the risk is further exacerbated due to several physiological processes (Rah et al. 2021). A diverse diet, including high protein and micronutrient sources, is essential to ensure proper physical and cognitive growth, particularly in early childhood. Nutrient-dense food like fruit and vegetables, legumes, dairy, eggs, and seafood must be included in larger portions while providing supplementary meals through nutrition delivery centers and school feeding programs.

In terms of data availability, the lack of micronutrient-level data at the population level is a considerable barrier to understanding the gravity and pattern of the regional burden. In addition, inadequate knowledge is often a more significant determinant of malnutrition than the lack of food (Romanos-Nanclares et al. 2018). Therefore, disseminating knowledge and awareness about healthy diets is critical to educating parents and caregivers and reducing the risk in infants and young children. Policies should consider geographical and sociocultural factors with collaboration with agrifood systems stakeholders, including local government and civil society institutions, while establishing public-private partnerships.

References

Afridi, F. 2010. Child Welfare Programs and Child Nutrition: Evidence from a Mandated School Meal Program in India [2]. Journal of Development Economics 92(2): 152–165.

Chakrabarti, S., A. Kishore, and D. Roy. 2018. Effectiveness of Food Subsidies in Raising Healthy Food Consumption: Public Distribution of Pulses in India [3]. American Journal of Agricultural Economics 100(5): 1427–1449.

FAO, IFAD, UNICEF, WFP, and WHO. 2022. The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2022 [4]. FAO.

Gillespie, S., J. Harris, N. Nisbett, and M. van den Bold. 2021. Stories of Change in Nutrition from Africa and Asia: An Introduction to a Special Series in Food Security [5]. Food Security 13(4): 799–802.

Kumari, S., S. Shukla, and S. Acharya. 2022. Childhood Obesity: Prevalence and Prevention in Modern Society [6]. Cureus 14(11): e31640.

Nugent, R., C. Levin, J. Hale, and B. Hutchinson. 2020. Economic Effects of the Double Burden of Malnutrition [7]. The Lancet 395(10218): 156–164.

Pinstrup-Andersen, P. 2007. Agricultural Research and Policy for Better Health and Nutrition in Developing Countries: A Food Systems Approach [8]. Agricultural Economics 37: 187–198.

Popkin, B. M., C. Corvalan, and L. M. Grummer-Strawn. 2020. Dynamics of the Double Burden of Malnutrition and the Changing Nutrition Reality [9]. The Lancet 395(10217): 65–74.

Rah, J. H., A. Melse-Boonstra, R. Agustina, R., K. G. van Zutphen, and K. Kraemer. 2021. The Triple Burden of Malnutrition Among Adolescents in Indonesia [10]. Food and Nutrition Bulletin 42(1_suppl): S4–S8.

Romanos-Nanclares, A., I. Zazpe, S. Santiago, L. Marín, A. Rico-Campà, and N. Martín-Calvo. 2018. Influence of Parental Healthy-Eating Attitudes and Nutritional Knowledge on Nutritional Adequacy and Diet Quality among Preschoolers: The SENDO Project [11]. Nutrients 10(12), 1875.

Sawaya, A. L., P. Martins, D. Hoffman, and S. B. Roberts. 2003. The Link between Childhood Undernutrition and Risk of Chronic Diseases in Adulthood: A Case Study of Brazil [12]. Nutrition Reviews 61(5): 168–175.

Trivedi, T., J. Liu, J. Probst, A. Merchant, S. Jhones, and A. B. Martin. 2015. Obesity and Obesity-Related Behaviors among Rural and Urban Adults in the USA. Rural and Remote Health 15(4), 3267.

White, J. M., F. Bégin, R. Kumapley, C. Murray, and J. Krasevec. 2017. Complementary Feeding Practices: Current Global and Regional Estimates [13]. Maternal & Child Nutrition 13, e12505.

World Health Organization (via World Bank). n.d. Our World in Data [14] (accessed 29 November 2022).