The latest Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change report, Global Warming of 1.5 ºC [1], notes the importance of mobilizing green finance for limiting global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius and preventing catastrophic climate change. In line with this, some countries have been implementing policies to support green bonds. Green bonds are debt securities whose proceeds are used to fund environmental projects, including climate change mitigation and adaptation. Therefore, unlike conventional bonds, green bonds finance projects with clear environmental benefits (ICMA 2018).

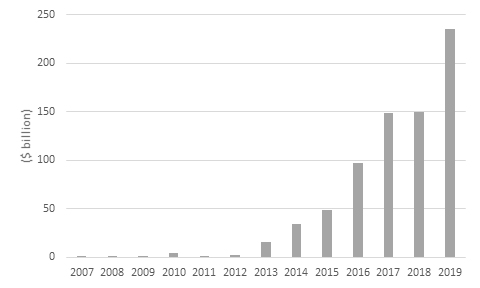

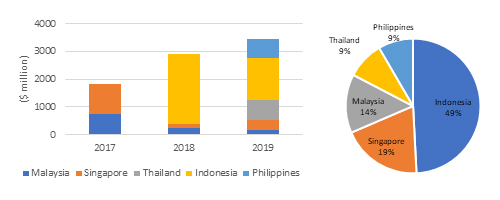

The issuance of green bonds around the world has grown rapidly, from $3.4 billion in 2012 to $235 billion in 2019 (Figure 1). Green bonds were first listed in the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) in 2017, and issuances in ASEAN grew from $1.8 billion in 2017 to $3.4 billion in 2019. The total value of green bonds issued in ASEAN reached $10.2 billion in June 2020.

Since 2017, around 1.2% of all green bonds have been listed in ASEAN. Green bonds proceeds have been used mostly to fund energy projects globally, including renewable energy and energy efficiency projects. However, in ASEAN, primarily in Singapore and Malaysia, proceeds from green bond issuances have been used mostly to fund green buildings. Green bond issuers are dominated by the financial sector and the government. The renewable energy and power generation sectors are underrepresented both in ASEAN and the world. In ASEAN, Indonesia leads green bond issuance by cumulative bond value. Most of the issuances in Indonesia have been by the government. The issuance of green bonds by governments is not unique to ASEAN, and globally 37% of all green bonds have been issued by governments.

Azhgaliyeva, Kapoor, and Liu (2020) provide a review of the policies supporting green bonds in the three largest issuing countries in ASEAN, i.e., Singapore, Malaysia, and Indonesia (Figure 2). The Monetary Authority of Singapore (MAS) launched a Green Bond Grant Scheme (GBGS) in 2017. The GBGS subsidizes green bond issuances by covering the cost of the external review for labeling bonds as “green.” This scheme catalyzed green bond issuances in Singapore as the cost of external review had been a significant hindrance in issuing green bonds. The subsidy was found to be successful, and the MAS extended it by 3 years until 2023. Singapore also decided against formulating its own national green bond standards and instead made the decision to accept any internationally recognized standards. Singapore’s GBGS also did not set restrictions on currency. This gave a boost to listing green bonds on the Singapore Stock Exchange (SGX) by issuers from around the world.

Similarly, Malaysia launched the Sustainable and Responsible Investment Sukuk Grant to partially cover the additional costs of issuing green bonds, such as the external review cost. Indonesia has instituted a Green Bond and Green Sukuk Framework that outlines eligible green projects for which green bonds can be issued. It has not implemented a green bond grant, but the government itself issued a high value of green bonds to kick-start the market.

Due to differences in the design of green bond policies in Singapore, Malaysia, and Indonesia, there have been different outcomes. Singapore, for instance, lets issuers from any entity list their bonds in any currency if the bonds are compliant with any internationally recognized green bond standard. This has helped to promote Singapore’s reputation as a green finance hub, but the policy design can be seen to be less effective if the objective was to promote projects that bring environmental benefits locally or achieve Intended Nationally Determined Contributions (INDCs). This is because the proceeds of green bonds listed on the SGX have been used to refinance (repay) past loans or to finance projects abroad.

The proceeds used to finance green projects abroad could bring environmental benefits globally but not necessarily contribute to the INDCs. Thus, it could be harder to achieve the INDCs if the eligibility criteria of policies do not limit projects only to domestic ones. The use of proceeds for refinancing green projects, on the other hand, could bring environmental benefits. Further research is needed to investigate the impact of refinancing projects.

Policy implications

Appropriate policy design is crucial for achieving a policy’s stipulated objectives, and these objectives must, therefore, be clearly defined before designing a green bond policy. The following recommendations are provided by Azhgaliyeva, Kapoor, and Liu (2020) for policy makers on the design of green bond policies:

- Policy makers should choose the design of green bond policies based on the objective, such as to achieve the INDCs or promote local green finance. Some policies can have conflicting qualification criteria, such as criteria on the project location or the use of the proceeds for refinancing.

- Green bond policies that aim to achieve the INDCs should restrict the eligibility criteria of projects to only domestic projects and limit the use of green bond proceeds for refinancing.

Figure 1: Global Green Bond Issuances

Source: Authors’ own elaboration using Bloomberg terminal data.

Figure 2: Green Bond Issuances in ASEAN, 2017–2019

Source: Azhgaliyeva, Kapoor, and Liu (2020).

Read the working paper here [2].

_____

References:

Azhgaliyeva, D., A. Kapoor, and Y. Liu. 2020. Green Bonds for Financing Renewable Energy and Energy Efficiency in Southeast Asia: A Review of Policies [2]. ADBI Working Papers Series No. 1073.

De Coninck, H., et al. 2018. Strengthening and Implementing the Global Response [1]. In Global Warming of 1.5°C. An IPCC Special Report on the Impacts of Global Warming of 1.5°C above Pre-Industrial Levels and Related Global Greenhouse Gas Emission Pathways, in the Context of Strengthening the Global Response to the Threat of Climate Change, Sustainable Development, and Efforts to Eradicate Poverty, edited by V. Masson-Delmotte et al.

International Capital Market Association (ICMA). 2018. Green Bond Principles: Voluntary Process Guidelines for Issuing Green Bonds [3]. June. ICMA.