Central Asia has for centuries been seen as a neglected Russian “backyard,” but international interest in the region has increased over the last two decades because of its vast stores of energy and natural resources. But to achieve a brighter future the region must pursue economic integration.

In the early 1990s, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyz Republic, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan1 became independent countries with the collapse of the Soviet Union. The abrupt separation from Moscow, the sudden interruption of economic relations under the Soviet Union, and the unprepared transition from state-directed to market economy created a deep economic crisis in all five countries. The beginning of this century saw their economic systems change and stabilize—but this occurred as these countries disclosed strong authoritarian trends.

Central Asia today

In Turkmenistan, a market economy exists only marginally, and the political system is dictatorial. Authoritarian governments in Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan are dominated by family clans who have implemented limited economic reforms. Tajikistan’s oligarchy took power after a bloody civil war whose consequences are preventing an economic recovery—making it one of the world’s poorest countries. Kyrgyz Republic is the only country that has pursued drastic political and economic reforms. Kyrgyz democracy is stabilizing, offering hope for a robust political framework to revive the economy.

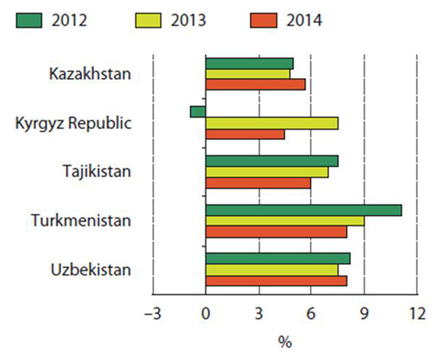

Central Asia’s impressive growth

These five countries have achieved impressive economic results with relatively high growth rates over the last ten years based on natural resources underpinned by rising global prices for those exports. The reason for the high growth rates: Central Asia became attractive to the EU and the US, as well as other Western countries and the People’s Republic of China (PRC) as providers of energy and natural resources. But his rapidly growing foreign economic and political engagement in the region has led to a geostrategic rivalry with Russia in Central Asia.

Central Asia GDP growth

Source: Asian Development Outlook Database

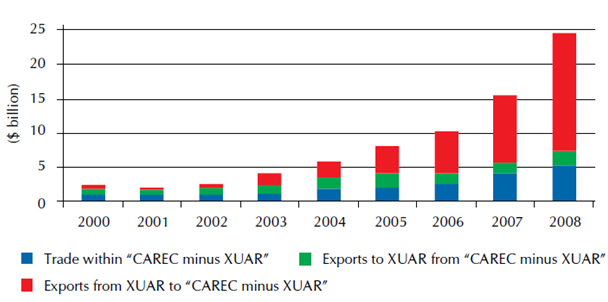

Central Asian countries have relatively small economies that are dependent on the export of a handful of commodities, and their trade is concentrated on a small number of countries outside the region. Nevertheless, growth rates of exports and imports have been impressive, while the trade in manufactured goods and participation in global production networks have been negligible. This dependence on a small number of exports and trade partners creates vulnerability to changes in import demand and other external shock risks.

Trade Growth in CAREC Member Countries 2000–2008 ($ billion)

Source: CAREC 2010.

Note: CAREC covers the membership of the Central Asia Regional Economic Cooperation Programme before enlargement in 2010 (Afghanistan, Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyz Republic, Mongolia, PRC, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan). CAREC minus XUAR excludes Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region, PRC.

Intraregional Trade Shares in Asia

Source: ADB 2010

Despite its limited economic integration, Central Asia has nevertheless maintained impressive export growth. However, a more integrated Central Asian trade block could create valuable synergy and strengthen its negotiating power on trade agreements, as well as offer greater protection from arbitrary sanctions by major trading partners.

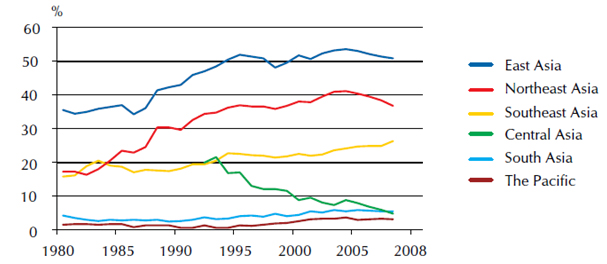

Outlook for intraregional trade

Intraregional trade in Central Asia has also grown. However, despite rapid growth the share of intraregional trade in Central Asia relative to the region’s trade, which plummeted after independence, has not reached pre-independence importance in relative terms. But once intraregional trade and investment barriers fall, intraregional trade opportunities will rise and tap into the great growth potential in intraregional Central Asian trade and investment.

Impeding intraregional and external trade are Central Asia’s deficient transport networks, which drive up costs and hamper transport and logistics services in the region. Expanded regional integration in transport networks and logistics services would save time and money at border crossings and shorten transport routes. This would boost trade in the region by reducing transit costs of the Eurasian overland route and increasing the attractiveness of Central Asia as an alternative “Eurasian traffic bridge” to maritime transport—which would be very much in the geostrategic interest of Eurasian trade partners EU and the PRC. These factors therefore support far-reaching Central Asia initiatives such as the “Silk Road Initiative” by the PRC.

Deeper integration would stabilize and strengthen economic growth and serve as a positive influence on the potential conflict situation in the south, especially Afghanistan and Pakistan—another geostrategic interest shared not only by the EU and the US, but also Russia and the PRC.

But regional integration requires political cooperation of the countries to be integrated. It is here where Central Asia has a fundamental deficit despite their mutual interests and despite their common history under Russian rule.

Nevertheless, several regional integration approaches should be explored.

Regional integration initiatives

The Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO) has, apart from the PRC and Russia, only member states from Central Asia, excluding Turkmenistan. SCO deals primarily with regional security issues, while economic integration receives only minimal attention. SCO is hindered by the limited commitment of the Central Asian members and by the growing rivalry between the PRC and Russia.

The EurAsian Economic Community (EurAsEC) includes Belarus and Russia, as well as Kazakhstan, Kyrgyz Republic, and Tajikistan. A customs union was started in 2011 that integrated Kazakhstan as the first member from Central Asia, and will be extended to Kyrgyz Republic, and Tajikistan. This far-reaching integration approach will be completed by the creation of a Eurasian Economic Union, announced in 2011.

In 2011, another integration project was launched called the Free Trade Area of Independent States, with Armenia, Belarus, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyz Republic, Moldavia, Russia, Tajikistan, and Ukraine, Uzbekistan as members. This agreement has not come into force yet.

The integration potential of EurAsEC and the Free Trade Area of Independent States, which are marked by a “post-Soviet aura,” is uncertain because of Russia’s dominant role.

The Central Asian Regional Economic Cooperation (CAREC) is an ADB supported initiative created in 1997 to encourage economic cooperation among countries in Central Asia. CAREC supports transport and transit corridors, trade facilitation, and communication and consultation among the ministries of member states. However, there have been few achievements beyond trade and energy development. The national development plans of the five CAREC members lack coherence between regional CAREC strategies and national planning.

Avoiding the “noodle bowl” effect

An additional economic integration challenge is that the above mentioned integration models overlap and pose a “noodle bowl” risk—once in force they would lead to increasingly complex treaty commitments and conflicting contractual obligations.

The lack of integrative spirit in the region offers a glimpse into the multilateral trade dimension. Kyrgyz Republic and Tajikistan are the only WTO members from Central Asia. Internal political conditions in Central Asian countries are factors for this dilemma. The oligarchies may fear that regional integration and economic opening would threaten their domestic sinecures and income sources. Central Asian economic integration has a chance, but regional governments are reluctant to take up the challenge because of mutual mistrust, and conflicting political and private interests.

Which integration model is best for overcoming regional reluctance and guaranteeing the greatest economic and political benefits for Central Asia?

CAREC, with its focus on economic integration, offers the best choice. CAREC’s inclusion of Afghanistan and Pakistan is consistent with the geostrategic interests to gain the stabilizing effects from Central Asia’s economic integration for these politically fragile and economically weak neighbor countries. In addition, CAREC includes only the PRC as a global trade actor of economic importance for the region. This is understandable because the PRC has replaced Russia as the region’s top trade partner with an annual PRC–Central Asian trade volume of $46 billion. But Russia will resist being pushed out of the economic and political sphere of Central Asia. To avoid confrontation with Russia and dependence on the PRC it is best to take Russia “onboard” CAREC, or at least invite it to join an economic partnership agreement in form of a “CAREC plus” approach—an offer that may be difficult for Russia to resist.

When taking additionally onboard the above mentioned economic and geostrategic interests of the US and the EU it makes sense to go even further to a CAREC+3 approach (CAREC plus Russia the EU and the US). East Asia’s highly successful ASEAN+3 model could provide valuable inputs.

Conclusion

CAREC+3 would not only mitigate a one-sided CAREC dependence on China. It would also provide China and +3 associates with a better basis to use theirpolitical and economic input into the region as leverage against the anti-integration reluctance among the region’s governments and in strong support of a more consequent regional integration in Central Asia.

This could support the aim of Central Asian governments, neighboring countries, and international partners to bolster the region against destabilization from a broader invasion of extremism and terrorism, primarily from the south. This congruence of political and economic interests would create a promising base and an incentive among CAREC members and +3 associates to work together under CAREC+3 for a more integrated, prosperous, and stable region. The various Silk Road initiatives offer good starting points for revitalizing Central Asia’s integration spirit from outside, but they have to be carried out in a balanced, consistent, and coordinated way to reduce risks of rivalry and imbalances as well as to take onboard the strategic concerns and interests of all relevant political actors. A broad and coherent CAREC+3 approach can fulfill the vision of an economically integrated and prosperous Central Asia.

_____

1 I chose a narrow geographic definition of Central Asia to include Kazakhstan, Kyrgyz Republic, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan, and exclude Afghanistan, Mongolia, and Pakistan with their complex political and economic challenges.

It depends on the acceptance of the people.However,it is a promising future because it will enhance the economic activities of the entire people of the integrated countries involved in it.