The United States’ “pivot to Asia” has been intensely discussed over the last years. But recently, a new pivot model has come up: the Russian Federation’s pivot to Asia. This article analyzes this topic from an economic perspective by asking: Is the Russian economy really about to shift its focus thus far centered on the European Union (EU) to Asia?

The following events have been heating up this discussion:

- In early 2014, the crisis between the Russian Federation and Ukraine started in Crimea and then spread into Eastern Ukraine. It prompted the EU and the Russian Federation to impose economic sanctions against each other which almost took on the dimension of an “open trade war.” They have not been lifted yet with increasing negative consequences especially for the Russian economy.

- In May 2014, the Russian Federation and the People’s Republic of China (PRC) signed a 30-year natural gas deal worth $400 billion which turned out to be the single largest trade deal ever in history.

Let us first take a brief look into the Russian Federation’s existing economic relations with the EU and with Asia before turning to its strategy vis-à-vis Asia. Figures on total trade turnover as well as on foreign direct investment (FDI) quickly lead to the conclusion that at the moment the EU is by far the Russian Federation’s most important economic partner worldwide.

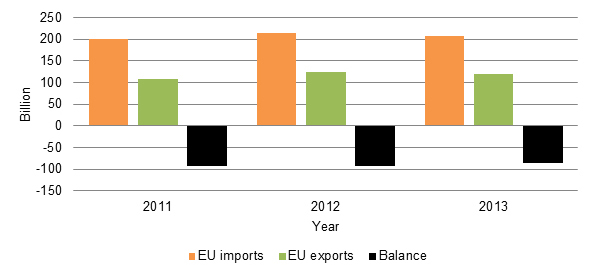

Total trade turnover between the Russian Federation and EU amounted to roughly $440 billion, with EU imports worth more than $268 billion and EU exports worth almost $157 billion in 2013 (see Figure 1 for trade in goods).1 That means that about half of all Russian foreign trade takes place with the EU. This refers primarily to energy trade: the EU covers around 20% of its oil supply and about 45% of its natural gas supply with imports from the Russian Federation. The EU exports primarily machinery and transport equipment, chemicals, as well as agricultural and textile products to the Russian Federation.2

Figure 1: EU–Russian Federation trade in goods (euro billion)

Source: European Commission. http://ec.europa.eu/trade/policy/countries-and-regions/countries/russia/ (accessed 20 August 2014).

After steep growth rates had come to a stop in mid-2008 (caused by the global economic crisis and unilateral measures adopted by the Russian Federation), EU–Russian trade resumed its growth reaching record levels in 2012.3

Figure 2 shows the current size of Russian trade relations with Asia, which gives a much more modest picture:

Figure 2: Russian Federation’s key trading partners in Asia ($ billion)

Source: 2013 Russian Foreign Trade Statistical Bulletin. http://rt.com/business/157092-east-west-russia-trade/ (accessed 6 May 2014).

Apart from Kazakhstan and Turkey, the Russian Federation’s economic relations in Asia focus regionally on Northeast Asian countries. The Russian trade turnover with Northeast Asia accounted for around $148 billion in 2013, with the PRC (trade turnover of almost $90 billion in 2013) clearly the top single trade partner in the subregion. The trade turnover with other Asian countries such as India hardly crosses the $15 billion threshold. In other words, the trade turnover with Asia (particularly East Asia) clearly lags behind the roughly $440 billion of the EU–Russian trade turnover of the same year.

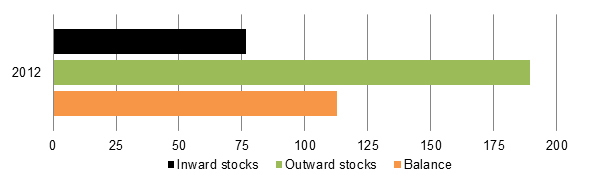

In parallel, about 75% of FDI flowing into the Russian Federation stems from EU investors which makes the EU the most important foreign investor in the country (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Foreign direct investment stock with the Russian Federation from EU perspective (euro billion)

Source: European Commission. http://ec.europa.eu/trade/policy/countries-and-regions/countries/russia/ (accessed 20 August 2014).

In 2012, EU outward FDI to the Russian Federation reached an accumulated level of almost $250 billion. In 2012 alone, FDI from the EU going to the Russian Federation reached a level of more than $40 billion whereas, FDI from the PRC only accounted for $0.5 billion (with an exceptional $0.6 billion FDI from Singapore and $0.12 billion from the Republic of Korea).

Outward FDI flows from the Russian Federation to the EU give an analogous picture having piled up to an accumulated level of almost $100 billion in 2012 with the Netherlands, Luxemburg, the United Kingdom, and Germany as main EU target countries. In comparison, the Russian Federation’s investment flows to Asia play in a much lower league: They focus on the PRC where up to 2012 they achieved a level between $1.5 billion4 and $4 billion5 depending on the data source.

From the data on total trade turnover as well as on FDI, we can draw a clear conclusion: in comparison to the Russian Federation’s rather limited economic relations with Asia, particularly East Asia, the EU holds a much more prominent role and will remain—at least in the medium term—a very important factor for the Russian economy. This is supported by the fact that the core of the Russian Federation’s industrial production is located in its European part. The quantity and quality of infrastructure there are generally much higher than in the vast Siberian territory belonging to Asia.

Nonetheless, the Russian Federation’s economic opening to Asia started long before the confrontation with the EU over Ukraine. The Russian Federation had already become a member of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) Regional Forum (ARF) in 1994 and became a member of the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) in 1998 (it even chaired the APEC Summit in Vladivostok in 2012). It joined the Asia–Europe Meeting (ASEM) in 2010 and the East Asia Summit in 2011.

The motives are clear: three quarters of Russian territory are in Asian Siberia which has lost 90% of its industrial production and 25% of its population since the 1990s. The Russian Far East does not only offer energy and mineral resources but also agricultural products, for all of which there is a huge demand in East Asia’s industrialized countries with the PRC at the top. So the Russian Federation needs its East Asian neighbors to develop its Far East. And not to forget: since before the Ukraine crisis, the EU had already questioned the Russian Federation’s privileged role in EU energy markets by starting to turn increasingly to alternative energy suppliers such as North Africa or Central Asia and by boosting liquefied natural gas (LNG) imports, renewables, and domestic supplies such as from the United Kingdom. Understandably, the Russian Federation has also begun to look for other potential customers to better balance a possible reduction of EU demand. One example is its plan for an energy community with its Northeast Asian neighbors leading to the aforementioned long-term energy contract with the PRC which is likely to be followed soon by another big deal with Japan. In the infrastructure context, President Putin has been pushing for a Russian “iron silk road” project connecting the trans-Siberian railways with the trans-Korean railways.6

In contrast, it is a fact that all those projects seem to have so far been run without a coherent strategy and consequent implementation. Apart from chairing the 2012 APEC summit, the Russian Federation’s visibility and commitment have been very limited with respect to better economic integration with its Asian neighbors. The country has free trade agreements (FTAs) with former Soviet republics in the Caucasus and Central Asia but no FTA in the rest of Asia. Although it has signaled interest in an FTA with ASEAN, it has so far restricted its efforts only to bilateral negotiations with Viet Nam. The Russian Federation’s participation in the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO) and the Greater Tumen Initiative have not led to remarkable integration results either and show how achieving further progress toward economic integration in Northeast could be a staggering feat.

The problem is aggravated by the fact that the lack of commitment on the Russian side is complemented by a lack of initiative on the Asian side, perhaps partly influenced by the assessment of the Russian Federation as an additional potential strategic competitor in East and Central Asia.

On the other hand, Russian and Asian interests are consistent: the Russian Federation needs Asia’s emerging economies as buyers for its mineral resources and agricultural products from Siberia—now even more desperately given damaged relations with its main partner the EU. The Russian Federation will not be able to quickly replace trade and FDI relations with the EU by trade and FDI with Asia. Via a closer economic partnership with Asia, however, it will be able to better balance the EU’s dominant role and better diversify its economic relations. From Asia’s perspective, stronger economic relations with the Russian Federation may generate additional supply for its huge appetite for energy and mineral resources as well as for agricultural products, but they may also open new transcontinental transport bridges to Europe.

So we can definitely expect the Russian Federation to become more foreceful and aggressive in its approaches for closer economic partnerships, especially with Northeast Asian countries. The Russian Federation will probably test both ways: bilateral agreements and access to Asian regional integration alliances. Both will require a much more consistent Russian strategy and a much bigger commitment to compromise. From its role in the Eurasian Economic Community (EurAsEC), the Russian Federation is used to playing the economically predominant leader. In Asia, it is the reverse—and the negotiations for the abovementioned gas deal with the PRC in May 2014 have proved that. The Russian Federation is “the new kid on the block” facing strong and tough Asian negotiating parties. And even when dealing with a small economy like Mongolia with whom Russian ties still run deep from the former Soviet era, it has to face competition from other mighty neighbors like the PRC.

Finally, the question of if and how fast the Russian Federation will be able to leave the economic “corset” of its extreme trade and investment dependency on Europe still remains.

Conversely, the Russian Federation’s pivot to Asia is an economic chance for countries there. It is therefore also up to them to find a suitable strategy for how to better integrate the Russian Federation. Approaches like an FTA with ASEAN, specifically one between the ASEAN Economic Community and the Russia Federation, a stronger focus of the SCO on regional economic integration, and even a revitalization of the former PRC initiative for a Northeast Asian FTA (NEAFTA) deserve a closer look in order to help Asia’s economies draw the best possible profit from this pivot.

_____

1 Taken from European Commission. http://ec.europa.eu/trade/policy/countries-and-regions/countries/russia/ (accessed 20 August 2014).

2 Taken from Federal Foreign Office of Germany. www.auswaertiges-amt.de/DE/Aussenpolitik/RegionaleSchwerpunkte/Russland (accessed 19 August 2014).

3 See note 1.

4 United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) Bilateral FDI Statistics 2014, download data by country, Russian Federation, Table 1, based on data from the Bank of Russia.

5 UNCTAD Bilateral FDI Statistics 2014, download data by country, People’s Republic of China, Table 2, based on data from the Ministry of Commerce.

6 See RT. http://rt.com/business/putin-lobbies-iron-silk-seoul-677/ (published 13 November 2013).